Muon-capture measurement backs QCD prediction

The rate at which protons capture muons has been accurately measured for the first time by the MuCap collaboration at the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) in Switzerland. This process, which can be thought of as beta decay in reverse, results in the formation of a neutron and a neutrino. The team has also determined a dimensionless factor that influences the rate of muon capture, which was found to be in excellent agreement with theoretical predictions that are based on very complex calculations.

Muons are cousins of the electron that are around 200 times heavier. Beta decays demonstrate the weak nuclear force in which a neutron gets converted into a proton by emitting an electron and a neutrino. Now, replace the electron with the heavier muon and run the process backwards: a proton captures a muon and transforms into a neutron while emitting a neutrino. This process – known as ordinary muon capture (OMC) – is crucial to understanding the weak interaction involving protons.

The proton and the weak force

The proton's interaction with the weak force is explained by the chiral perturbation theory (ChPT) – an approximation of quantum chromodynamics (QCD) applicable at low particle energies. At such energies, the weak interaction inside a proton is affected by the presence of the strong force. The strength of this weak interaction is determined by certain coupling constants, which must be experimentally established.

"Essentially, these constants represent the basic properties of the proton, and describe the fact that it is not point-like but has a complex internal structure," says Peter Kammel from the University of Washington, Seattle, one of the physicists involved in this research. Three of these dimensionless parameters have been previously measured, but attempts at measuring the fourth, known as "pseudoscalar coupling", provided conflicting results, until now. "Of course," continues Kammel, "the pseudoscalar coupling constant could be calculated quite precisely by using chiral perturbation theory, which predicts a value of 8.26 ± 0.23." In order to measure its value, the physicists had to first determine with a high accuracy the rates at which muon capture takes place.

Capture versus decay

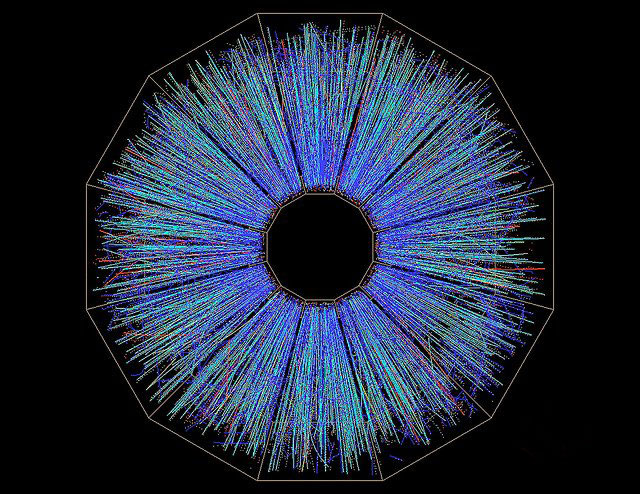

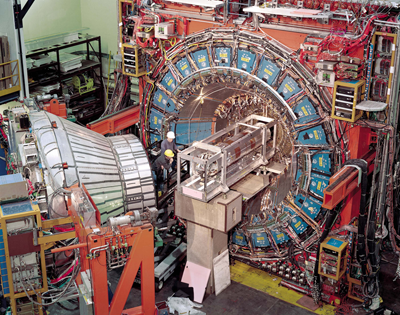

The muons used in the study were produced by smashing protons into carbon targets at an energy of 590 MeV. These collisions produce both positive and negative pi-mesons (or pions), which promptly decay into positive and negative muons, respectively. Muons with an energy of 5.5 MeV are then fired into a MuCap time projection chamber (TPC), which contains ultrapure hydrogen gas at 10 bar.

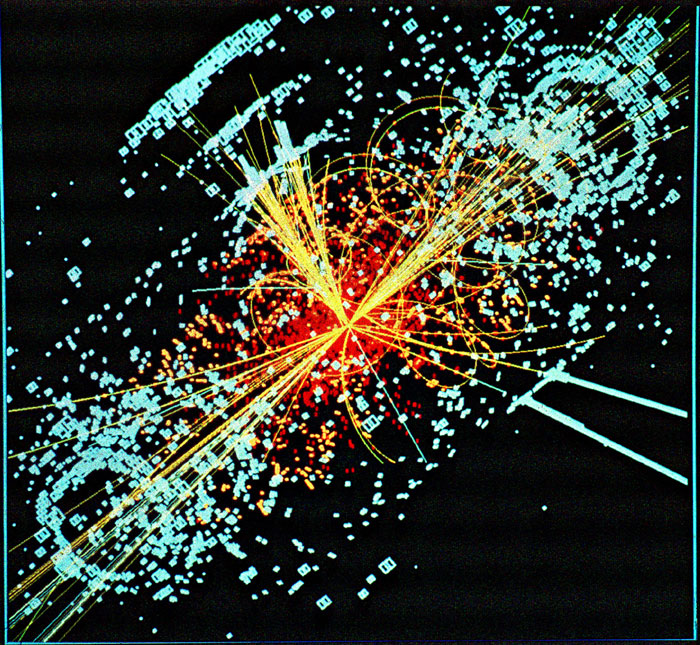

The negative muons supplant the electrons that orbit the hydrogen nuclei to form a proton–muon bound state, while the positive muons remain free. A small fraction of the bound muons – around 0.16% – will get captured by the proton and disappear, as they form a neutron and a neutrino. All of the remaining muons, both positive and negative, will decay after about two millionths of a second into electrons and neutrinos. The decay times were calculated precisely by measuring the time between the muons entering the TPC and the electrons from the decay exiting the chamber. These decay times were then compared to the well-known free muon decay rate and the difference between the two determines the elusive muon-proton capture rate.

A total of around 12 billion decay events involving negative muons were detected, corresponding to 30 TB of raw data that were analysed. The analysis was performed blind to prevent any unintentional bias from distorting the results and, following the unblinding, the measured muon-capture rate was found to be 714.9 ± 5.4 (stat) ± 5.1 (syst) s–1.

Confirming predictions

Using this figure, the team could calculate the value of the pseudoscalar coupling constant, which worked out to be 8.06 ± 0.48 ± 0.28, consistent with the predictions of ChPT. Although experimental methods to determine the pseudoscalar coupling constant started in the 1960s, it was not until the MuCap experiment that the objective was achieved.

"The nucleon weak-interaction coupling constants played a significant role in understanding the weak and strong interactions," continues Kammel. "The modern description of the process we have investigated is based on ideas proposed by Yoichiro Nambu, for which he won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 2008." The approximate methods of calculation presented by ChPT agree very well with the experimental result, confirming yet another prediction of the Standard Model of particle physics.