To make a perfect lens – one that produces images at unlimited resolution – you need a very special material that exhibits "negative refraction". Or so researchers had thought.

Now scientists in the UK and Singapore have published experimental evidence that shows perfect lenses don't need negative refraction at all – and that a simpler solution lies in a 150 year-old design pioneered by James Maxwell. If true, the discovery could be a goldmine for the computer-chip industry, allowing electronic circuits to be made far more complex than those of today. However, the work is proving so controversial that the lead scientist has become embroiled in a fiery debate with other experts in the field.

The route to perfection

Until the turn of the century, perfect imaging was thought impossible. Light diffracts around features the same size as its wavelength, which should make it impossible for a lens to resolve details that are any smaller.

But in 2000 John Pendry of Imperial College London found a way to beat this "diffraction limit". He understood that, in addition to the light captured by normal lenses, an object always emits "near field" light that decays rapidly with distance. Near-field light conveys all an object's details, even those smaller than a wavelength, but no-one knew how to capture it.

Pendry's answer was negative refraction, a phenomenon that bends light in the opposite direction to a normal substance like glass. If someone could make such a negative-index material, he said, it would be able to reign in an object's near-field light, producing a perfect image.

It was a controversial prediction, but in 2004 researchers at the University of Toronto proved the sceptics wrong by creating a negative-index material and using it to focus radio waves beyond the diffraction limit. And that might have been where the story ended, except that negative-index lenses ultimately proved to be impractical for many applications. They absorb a lot of light, and only work within a wavelength's distance of the object.

Maxwell's fisheye

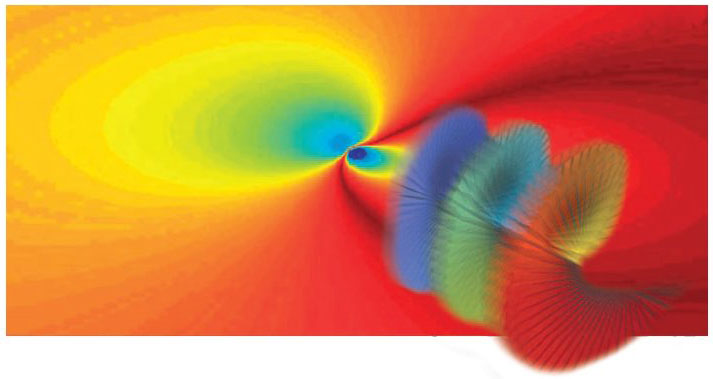

In 2009 Ulf Leonhardt of St Andrews University in the UK realized there may be another way forward. He had been examining a flat "fisheye" lens, first conceived by Maxwell in the mid 19th century, in which a unique refractive-index profile forces light rays to travel in circles, as though they were hugging the surface of an invisible sphere. Indeed, light rays emitted from an object anywhere on the flat surface would always meet at a point precisely opposite.

Leonhardt solved the standard equations of light propagation for the fisheye and came to a remarkable conclusion: all light, including the near field, is refocused at the image point as though it were travelling backwards in time to the source. In other words, said Leonhardt, the image would be the object's exact, perfect, replica.

The fisheye did have a slight problem. For one half of the lens, the change in refractive index implied light would have to travel faster than it does in a vacuum – a known impossibility. Leonhardt's solution again played on the symmetry: replace that half with a mirror, he said, so the semicircles of light on that side are simply reflected from the other.

But like Pendry's nine years before, the prediction met fast resistance. Within two months, Richard Blaikie of the University of Canterbury in New Zealand published a response claiming that any enhanced focusing would not be intrinsic to the fisheye, but an artefact left by having a "drain" where the image is. "An everyday example I can think about is a lightning rod, which concentrates electric fields around its sharp tip," says Blaikie. "Leonhardt and others somehow confuse this natural (and very well understood) field concentration with imaging."

A perfect illusion?

The drain, which is essentially a detector, was mentioned as a requirement in Leonhardt's paper. Yet he admits that he wasn't initially aware of its role – that it captures the image before the light continues on its circular track back to the source. "It turns out that perfect imaging is only possible when the image is detected; the perfect image appears, but only if one looks...Purists may call it an artefact, but if the 'artefact' creates a perfect image, it's a useful feature."

Others, including Pendry, were not convinced: at least five other papers have been published arguing against Leonhardt's prediction. However, in a paper published today in the New Journal of Physics, Leonhardt and colleagues from St Andrews and the National University of Singapore claim "unambiguous" proof that they have beaten the diffraction limit with the fisheye for microwaves.

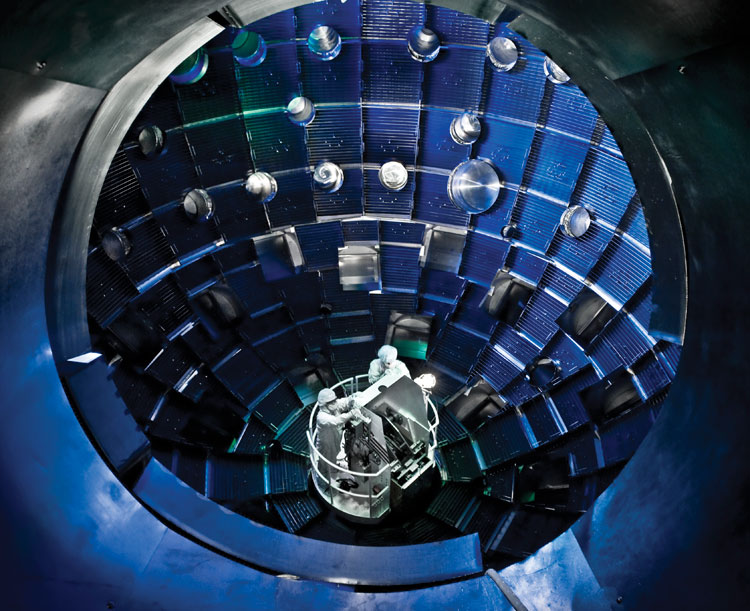

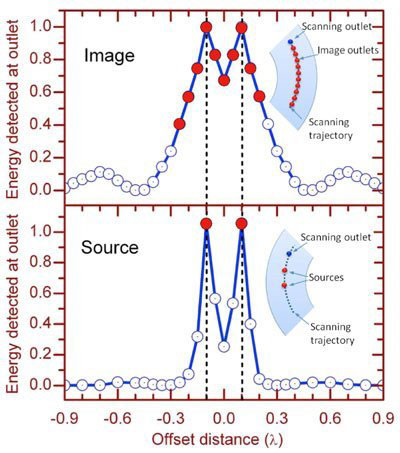

In its experiment, Leonhardt's group forms the fisheye's varying refractive index profile with concentric rings of copper, surrounded by a mirror. Microwaves enter on one side from a pair of cables just one-fifth of a wavelength apart, and travel across the rings to a bank of 10 cables, functioning as drains (see "Leonhardt's fisheye").

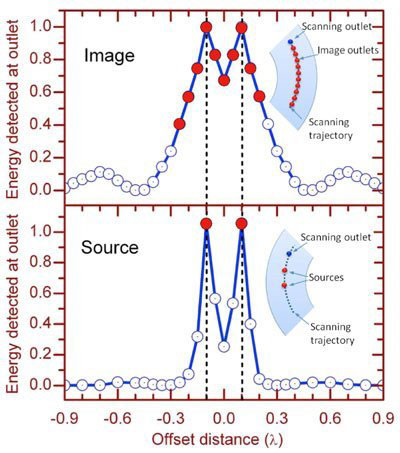

Crucially, the researchers show that the signal arriving at the bank is not smoothed out over all the cables, as would be the case in a normal, diffraction-limited lens. Instead, only those two drains precisely opposite the two cables register strong signals (see "Perfect evidence?"). For Leonhardt, this is proof of imaging beyond the diffraction limit, and the basis of a perfect lens. "The behaviour cannot be explained as an artefact of the drains," he adds, "because otherwise all 10 drains would register intensity spikes."

Clone wars

Yet despite this demonstration, all authors of the original arguments against Leonhardt's prediction told physicsworld.com that they are not convinced. Pendry believes the lens works only when the drains are a "clone" of the source, so that the near-field light is tricked into reappearing. "If the clone is removed, resolution degrades and is limited by wavelength as in a normal lens," he says. The need of a clone would make the lens useless for imaging features that are too small to see.

Leonhardt disagrees. His drain cables were half the length of the source cables, so were not clones, he says. Indeed, he believes that it would be possible to repeat the experiment for visible light, with photographic film recording the perfect image. And he has supporters: Matti Lassas, a mathematician at the University of Helsinki, Finland, thinks Leonhardt has answered his critics' arguments convincingly. The ideas are "true breakthroughs in transformation optics", Lassas says.

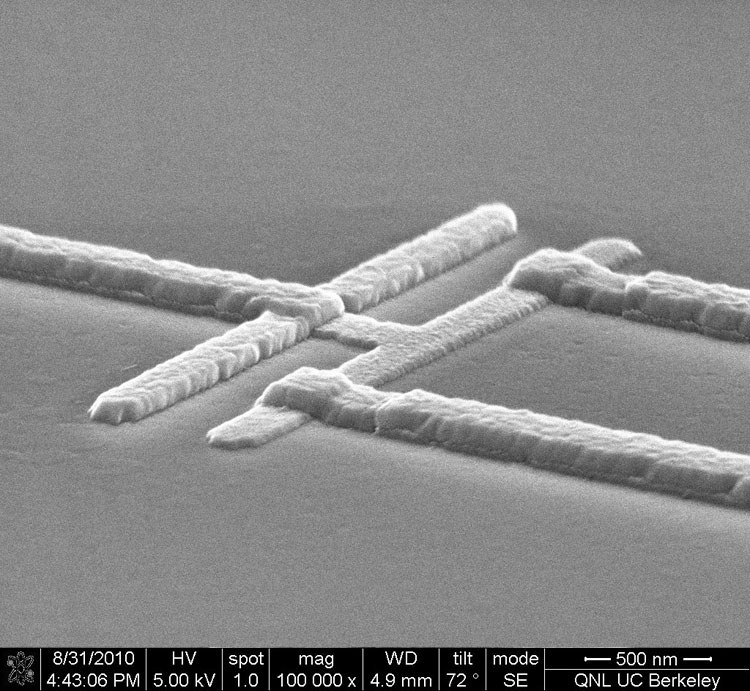

"It will take time and more experiments," says Leonhardt, "but I'm sure in the end even the most hard-nosed critics will be convinced that it works. Maybe they need to see a perfect photograph of fine structures that are otherwise impossible to see. Seeing is believing, but then it will be too late for the sceptics to be ahead of the game."