Dim, dense and dying, white dwarf stars might seem an unlikely place to seek Earth's twin. But an astronomer in the US says that planets orbiting such stars could support life for billions of years. Furthermore, white dwarfs are as numerous as the Sun-like stars that searches for extraterrestrial life currently target, so this finding adds billions of potential abodes for life to the galaxy.

"I was just thinking, `What would be an easy way to detect an Earth-like planet?'" says Eric Agol of the University of Washington in Seattle, who notes that finding planets as small as Earth is normally so difficult it requires an expensive space-based telescope. "That's what led me to white dwarfs."

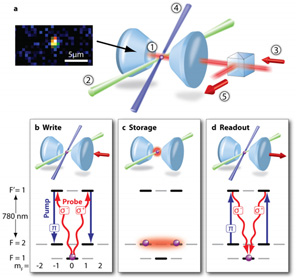

Conveniently, white dwarfs are small. Although a typical white dwarf has 60% of the Sun's mass, its diameter is little larger than Earth's. Thus, an Earth-sized planet can block nearly all the star's light, so even a 1 m ground-based telescope could detect the presence of a planet.

Offspring of red giants

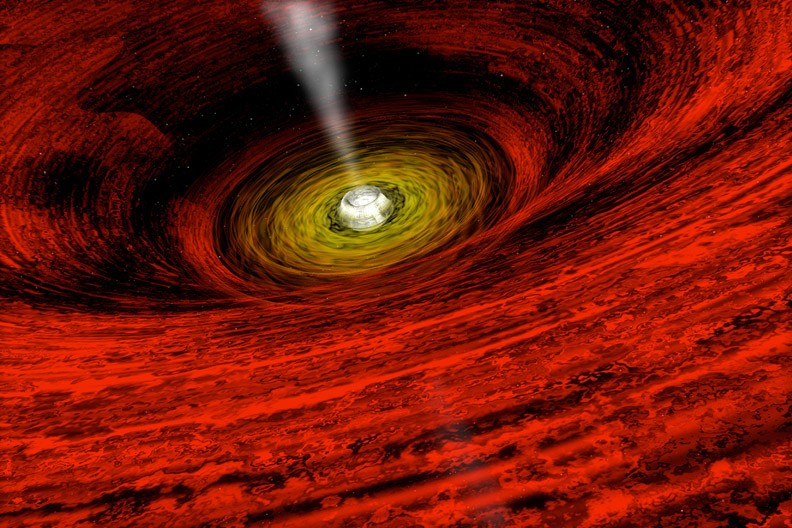

White dwarfs form from stars like the Sun, whose cores use nuclear reactions to convert hydrogen into helium. When the core gets too full of helium, the star will begin burning hydrogen outside the core, causing the star to expand and its surface to cool and redden, until the star becomes a red giant. Then the red giant will cast off its outer atmosphere, exposing its hot core.

That hot core is a white dwarf, which starts life at a temperature exceeding 100,000 K. It shines not from nuclear reactions but from its leftover heat. As the white dwarf emits light into space, the star cools and fades.

Agol says the most promising white dwarfs for habitable planets have surface temperatures between 3000 and 9000 K – comparable to the Sun's temperature of 5780 K. Such white dwarfs are fading only slowly, so they may give an orbiting planet billions of years of mild temperatures. "If you're on the surface of that planet, your star would look about the same angular size and about the same colour as the Sun," says Agol.

Goldilocks zone

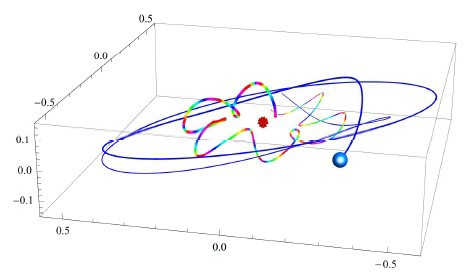

These white dwarfs emit 1/10,000 of the Sun's light, so a planet with terrestrial temperatures must be about 1/100 as far from its star as Earth is from the Sun. Unfortunately, a red giant would have engulfed such a close planet, but Agol says a planet could get kicked close to a white dwarf by the gravity of another planet – or even form there if gas encircled the white dwarf after its birth.

A habitable planet would eclipse its star for about two minutes, says Agol. He calculates that a white dwarf with 60% of the Sun's mass could have habitable planets that revolve every 4–32 hours. At shorter orbital periods, the planet is so close to the star that the star's tides tear the planet apart; at longer periods, the planet is too far from the star and too cold.

Whatever the period, a habitable planet around a white dwarf would have a permanent day side – where any life would presumably exist – and a permanent night side. That's because tides from the star would lock the planet so that the same side always faced the star, as with the Moon and the Earth.

No shortage of dwarfs

About 5% of all stars are white dwarfs. They are so common that two of them – Sirius B and Procyon B – reside within just a dozen light-years of the Sun. The chance that a planet in the habitable zone eclipses its star as seen from Earth is about 1%. Some 15,000 white dwarfs lie within 300 light-years of us, so if every star has one planet in the habitable zone, we should be able to detect 150 planets within that distance.

"It's a plausible idea, and it's very creative," says James Kasting of Pennsylvania State University in University Park. "I would never have thought about being able to detect habitable planets around white dwarfs."

"What's wonderful is if they're there, they're detectable," says Gregory Laughlin of the University of California at Santa Cruz. "It gives a plausible and completely new route to possibly looking at planets that might harbour Earth-like environments." Moreover, Laughlin says astronomers could easily study the planets' atmospheres, because the eclipses would be so deep.

Agol acknowledges trouble with one key ingredient for life – water. "This is one of the biggest problems: the planet starts out hot," he says, because the star did, and the heat may have driven away all the planet's water. "On the other hand, the Earth started out hot too." Water might reach the surface of the white dwarf planet through comet impacts and volcanic eruptions.