Pulsed lasers could make proton therapy more accessible

A table-top proton accelerator for medical therapy could be one step closer thanks to work done by physicists in Germany. The team's system is based on a compact Ti:sapphire laser, which fires ultrashort light pulses at a diamond-like foil to produce bunches of protons with energies of around 5 MeV. The team has shown that its device delivers radiation doses to biological cells that are similar to doses created by much larger conventional proton-therapy systems. The researchers say that the technique could also be used to study ultrafast processes in biology and chemistry.

Accurate delivery

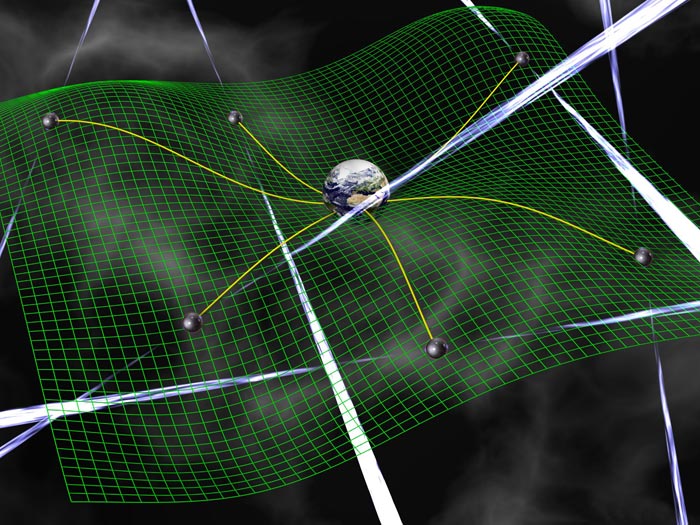

Protons – and other heavier ions such as carbon – show great promise for radiation therapy because when fired into living tissue, they deposit most of their energy at a very specific depth that depends on their initial energy. This is unlike X-rays and electrons, which tend to deposit energy over much larger regions of tissue. As a result, protons can be used to destroy tumours while leaving surrounding healthy tissue unharmed. The downside of proton therapy is that it requires the use of a large and expensive accelerator and can only be done at about 30 facilities worldwide. With the aim of offering proton therapy to more people, medical physicists are looking at how compact lasers could be used to create smaller and less costly proton sources. The basic idea is to fire short, intense laser pulses at a thin target, which liberates protons or other ions and accelerates them over distances as small as a few microns. Researchers have already shown that table-top femtosecond lasers with pulse energies of several joules can create proton beams with energies of up to 40 MeV.

Biological effectiveness

But before laser-driven ion beams can be used on patients, it is necessary to study how the proton pulses interact with living cells. In, particular scientists must compare the effectiveness of ultrashort-pulsed ion beams with that of continuous beams from conventional accelerators. With this aim, Jan Wilkens from the Technical University of Munich and colleagues have used a high-power table-top laser to generate nanosecond proton bunches that deliver single-shot doses of up to seven gray to living cells. This is equivalent to a peak dose rate of 79 Gy/s over a 1 ns interval, and such doses are sufficient for radiation therapy.

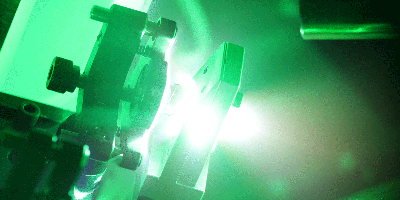

System set-up

The researchers used the ATLAS laser – a table-top Ti:sapphire laser that delivers 30 fs pulses – at the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics near Munich. Laser pulses with 0.4 J energy were focused to a 3 μm spot, yielding a peak intensity of 8 × 1019 W/cm2. This beam was used to irradiate diamond-like carbon (DLC) foils with thicknesses of 20 and 40 nm.

"The nanometre foils enabled a hundred-fold higher [proton] luminosity as compared to [standard] micron-thick targets," explains Jörg Schreiber, from Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, who was one of the team. "We have pioneered the application of nanometre DLC foils and it has paid off." The beamline included a miniature quadrupole doublet magnetic lens inserted behind the DLC foil to focus the protons at a distance of 1.2 m. A circular aperture is placed 810 mm from the target, in front of a dipole magnet that deflects the protons downwards. This avoids irradiation of the cells by X-rays created when the laser pulse slams into the target. The beamline is evacuated and to irradiate living cells, the proton bunch leaves the vacuum through a Kapton window and enters a customized cell holder.

Irradiating cancer cells

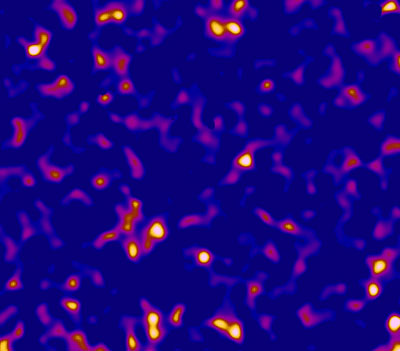

The researchers exposed single layers of human cervical cancer cells to protons generated in a single shot. The resulting dose distribution was measured using radiochromic film behind the cells. A microstructured grid on the cell holder enabled registration of the dose distribution with a spatial uncertainty of 21 μm. The team confirmed that cells were damaged by the protons using a chemical assay that detects the presence of broken strands of DNA.

Using these data, the team calculated the relative biological effectiveness (RBE) of the dose and found it to be similar to that of conventional proton beams at comparable energies. The researchers say that this work demonstrates the potential of small, high-repetition-rate lasers for creating intense pulse protons that are almost monoenergetic and contain relatively small amounts of background radiation.

Ultrafast studies

Beyond proton therapy, the researchers say that the proton source could be used for basic science: "The laser-driven beam could have impact as a tool in fast biological or chemical processes. Of special interest is the availability of other temporally synchronized laser-driven sources to perform pump probe experiments," they note. The team is now aiming to create beams with higher ion energies. "This requires more powerful lasers, which are currently under construction in our lab and elsewhere," Wilkens and Schreiber explain.