داغترین دمایی که تاکنون اندازهگیری شده است، منفیست

فیزیکدانان ذراتِ موجود در یک نمونهی گازی را وادار کردهاند که بر خلافِ داشتنِ مقادیرِ بسیار زیادی از انرژی، همچنان مقید باقی بمانند. به این ترتیب شمارِ ذراتِ موجود در ترازهای بالاترِ انرژی بیش از شمارِ آنها در ترازهای پایینتر است و این به این معناست که دمای این نمونهی گازی در مقیاسِ کلوین، زیرِ صفرِ مطلق است.

گرچه متناقض به نظر میآید، اما پژوهشگران با سردکردنِ یک نمونهی گازی و رساندنِ دمای آن به مقادیرِ منفی در مقیاسِ کلوین، توانستهاند بالاترین دمایی را که تابهحال اندازهگیری شده است، ثبت کنند. این پژوهش که چهارم ژانویه در مجلهی Science به چاپ رسیده به فیزیکدانان کمک میکند که در موردِ پدیدههای کوانتومی و یا حتی شکلِ ناشناختهای از انرژی که بر کیهان حکمفرمایی میکند (انرژیِ تاریک)، بیشتر بیاموزند. منفیبودنِ دمای یک سامانه در مقیاسِ کلوین نشاندهندهی حالتیست که در آن، شمارِ ذراتِ موجود در حالتهایی با انرژیِ بالاتر، بیشتر از ذراتیست که در حالتهایی با انرژیِ پایینتر هستند.

همانگونه که آخیم رُش (Achim Rosch)، فیزیکدانی از دانشگاهِ کُلنِ آلمان که در این کارِ پژوهشی همکاری نداشته توضیح میدهد: "ما همواره به دماهایی با اندازهی مثبت عادت داریم، درحالیکه هیچ مانعی برای منفیبودنِ دما وجود ندارد. انجامِ کارهای نامعمول همواره جذاب است". معمولا دما را به عنوانِ سنجهای برای اندازهگیریِ میانگینِ انرژیِ ذراتِ موجود در یک نمونه تعریف میکنیم. به عنوانِ مثال، انرژیِ مولکولهای آب که در دیگی جوشان قرار دارند به طورِ میانگین، بیشتر از انرژیِ مولکولهای آبی راکد است که در یک مکعبِ یخی قرار دارد. اما برای دانشمندانی که مواد را در مقیاسهای کوانتومی بررسی میکنند، دما به عنوانِ سنجهای برای چگونگیِ توزیعِ انرژی میانِ ذراتِ موجود در یک نمونه تعریف میشود. درست در دمایی کمی بالاتر از صفرِ مطلق (صفرِ کلوین یا 273- درجهی سلسیوس) تقریبا همهی ذرات موجود در یک نمونه، انرژیشان بسیار نزدیک به صفر است و ذرات تنها دارای جنبشهای بسیار اندکی هستند. اما با افزایشِ دما، تفاوتِ میانِ انرژیِ ذراتِ موجود در نمونه نیز افزایش مییابد، برخی از ذرات همچنان انرژیِ بسیار اندکی دارند اما ذراتِ دیگرِ نمونه در حالتهایی با انرژیِ بیشتر قرار میگیرند.

اُلریش اِشنایدِر (Ulrich Schneider) یکی از فیزیکدانانِ دانشگاهِ لودویک ماکسیمیلیان واقع در مونیخ است که برای انجامِ کاری شگرف، طرحی در دست دارد. او با فریبدادنِ ذراتِ موجود در یک نمونه، آنها را وادار کرده که با وجودِ داشتنِ مقادیرِ بسیار زیادی از انرژی، همچنان در حالتهای مقید باقی بمانند. به بیانِ دیگر، این پژوهشگر به جای آنکه با افزایشِ انرژی، ذراتی که دارای کمینه مقدارِ انرژی هستند (حالتی با دمای صفرِ مطلق) را به حالتهایی با انرژیِ بیشتر بفرستد، ذراتی با بیشینه مقدارِ انرژی را به میانِ حالتهایی با انرژیِ کمتر میکشاند. بنا به تعریف، چنین نمونهای در مقیاسِ کلوین دارای دمای منفی خواهد بود.

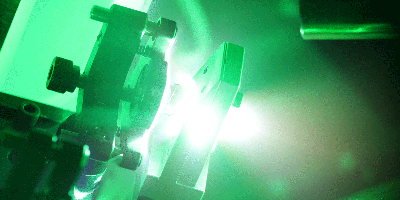

اعضای این گروهِ پژوهشی برای رسیدن به این هدف، ابتدا اتمهای پتاسیم را تا دمای چند میلیاردیومِ درجه بالای صفرِ کلوین، سرد میکنند. سپس با بهکارگیریِ چند لیزر و آهنربا، اتمها را وادار میکنند که به ترازی با انرژیِ بیشتر بروند. به این ترتیب Schneider و همکارانش با ایجادِ انبوهی از ذرات که در ترازهایی با انرژیِ بالا نگهداشته شدهاند، این نمونهی گازی را به دمایی در حدودِ چند میلیاردیومِ درجه زیرِ صفر کلوین میرسانند. این دما در واقع دمایی زیرِ صفرِ کلوین نیست چراکه بر خلافِ مقیاسِ فارنهایت و سلسیوس (که منفیبودنِ دما در آنها به معنیِ سردتر بودنِ سامانه است)، دمایی که در مقیاسِ کلوین منفیست اطلاعاتی دربارهی ترازهای انرژیِ ذراتِ موجود در یک سامانه به دست میدهد. در واقع نمونهی گازی که توسطِ این گروهِ پژوهشی آمادهسازی شده، بسیار داغ است چراکه بیشترِ ذراتِ این سامانه در ترازهایی با انرژیِ بالا قرار گرفتهاند. همانگونه که Schneider توضیح میدهد: "گرما همواره از جسمِ گرمتر به سوی جسمِ سردتر شارش مییابد. در این آزمایش نیز شارشِ گرما همواره از نمونهی گازی به سوی محیطِ اطراف است. در حقیقت این نمونهی گازی از هرچه در اطرافِ آن میشناسیم، گرمتر است".

بر خلافِ آنچه تاکنون گفته شد، این آزمایش بهخودیِخود یک ترفندِ جالبِ فیزیکی نیست. چیزی که توجهِ دانشمندان را به بررسیِ مواد در دمای منفی جلب میکند، ویژگیهای شگرفِ دیگریست که این مواد از خود نشان میدهند. مولکولهای موجود در یک نمونهی گازیِ معمولی، همواره در حالِ پخش شدن هستند و به دیوارههای ظرفی که در آن قرار گرفتهاند، نیرو وارد میکنند. اما یک نمونهی گازی با دمای منفی، دارای فشارِ منفی نیز هست که به این معناست که مولکولهای چنین گازی به جای آنکه منبسط شوند، بیشتر تمایل دارند روی یکدیگر فروبریزند. یافتنِ یک نمونهی گازی با فشارِ منفی ممکن است نقشِ مهمی را در حوزهای دیگر از فیزیکِ کیهانِ پیرامون ما ایفا کند: کیهانشناسان بر این باورند که انرژیِ تاریک، پدیدهای اسرارآمیز که انبساطِ شتابدارِ کیهان را سبب میشود، نیز دارای فشارِ منفیست. Schneider میافزاید: "با انجامِ آزمایشهای هرچه بیشتر دربارهی دمایِ منفی، که پدیدهای کوانتومیست، میتوان سرشتِ انرژیِ تاریکِ موجود در کیهان را هرچه بهتر شناسایی کرد".