String theory, which stretches back to the late 1960s, has become in the last 20 years the field of choice for up-and-coming physics researchers. Many of them hope it will deliver a "Theory of Everything"—the key to a few elegant equations that explain the workings of the entire universe, from quarks to galaxies.

Elegance is a term theorists apply to formulas, like E=mc2, which are simple and symmetrical yet have great scope and power. The concept has become so associated with string theory that Nova's three-hour 2003 series on the topic was titled The Elegant Universe.

Yet a demonstration of string theory's mathematical elegance was conspicuously absent from Nova's special effects and on-location shoots. No one explained any of the math onscreen. That's because compared to E=mc2, string theory equations look like spaghetti. And unfortunately for the aspirations of its proponents, the ideas are just as hard to explain in words. Let's give it a shot anyway, by retracing the 20th century's three big breakthroughs in understanding the universe.

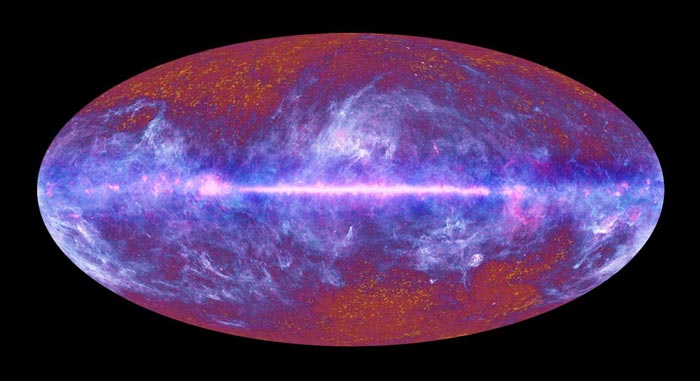

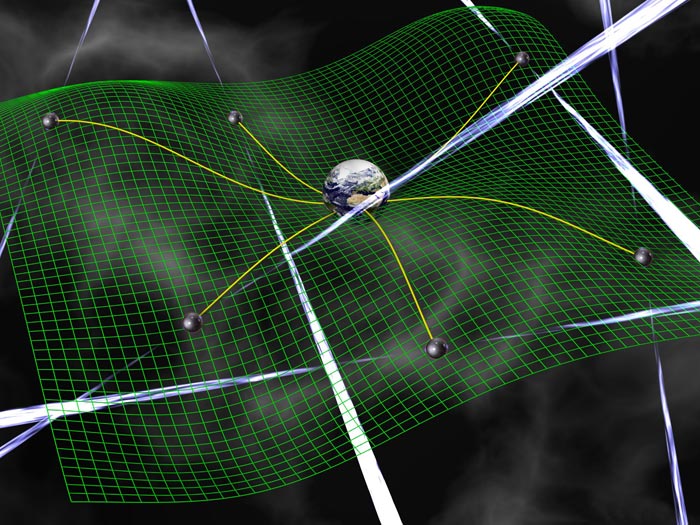

Step 1: Relativity (1905-1915). Einstein's Special Theory of Relativity says matter and energy (E and m in the famous equation) are equivalent. His General Theory of Relativity says gravity is caused by the warping of space due to the presence of matter. In 1905, this seemed like opium-smoking nonsense. But Einstein's complex math (E=mc2 is the easy part) accurately predicted oddball behaviors in stars and galaxies that were later observed and confirmed by astronomers.

Step 2: Quantum mechanics (1900-1927). Relativistic math works wonderfully for predicting events at the galactic scale, but physicists found that subatomic particles don't obey the rules. Their behavior follows complex probability formulas rather than graceful high-school geometry. The results of particle physics experiments can't be determined exactly—you can only calculate the likeliness of each possible outcome.

Quantum's elegant equation is the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. It says the position (x) and momentum (p) of any one particle are never completely knowable at the same time. The closest you can get is a function related to Planck's constant (h), the theoretical minimum unit to which the universe can be quantized.

Einstein dismissed this probabilistic model of the universe with his famous quip, "God does not play dice." But just as Einstein's own theories were vindicated by real-world tests, he had to adjust his worldview when experimental results matched quantum's crazy predictions over and over again.

These two breakthroughs left scientists with one major problem. If relativity and quantum mechanics are both correct, they should work in agreement to model the Big Bang, the point 14 billion years ago at which the universe was at the same time super massive (where relativity works) and super small (where quantum math holds). Instead, the math breaks down. Einstein spent his last three decades unsuccessfully seeking a formula to reconcile it all—a Theory of Everything.

Step 3: String theory (1969-present). String theory proposes a solution that reconciles relativity and quantum mechanics. To get there, it requires two radical changes in our view of the universe. The first is easy: What we've presumed are subatomic particles are actually tiny vibrating strings of energy, each 100 billion billion times smaller than the protons at the nucleus of an atom.

That's easy to accept. But for the math to work, there also must be more physical dimensions to reality than the three of space and one of time that we can perceive. The most popular string models require 10 or 11 dimensions. What we perceive as solid matter is mathematically explainable as the three-dimensional manifestation of "strings" of elementary particles vibrating and dancing through multiple dimensions of reality, like shadows on a wall. In theory, these extra dimensions surround us and contain myriad parallel universes. Nova's "The Elegant Universe" used Matrix-like computer animation to convincingly visualize these hidden dimensions.

Sounds neat, huh—almost too neat? Krauss' book is subtitled The Mysterious Allure of Extra Dimensions as a polite way of saying String Theory Is for Suckers. String theory, he explains, has a catch: Unlike relativity and quantum mechanics, it can't be tested. That is, no one has been able to devise a feasible experiment for which string theory predicts measurable results any different from what the current wisdom already says would happen. Scientific Method 101 says that if you can't run a test that might disprove your theory, you can't claim it as fact. When I asked physicists like Nobel Prize-winner Frank Wilczek and string theory superstar Edward Witten for ideas about how to prove string theory, they typically began with scenarios like, "Let's say we had a particle accelerator the size of the Milky Way …" Wilczek said strings aren't a theory, but rather a search for a theory. Witten bluntly added, "We don't yet understand the core idea."

If stringers admit that they're only theorizing about a theory, why is Krauss going after them? He dances around the topic until the final page of his book, when he finally admits, "Perhaps I am oversensitive on this subject …” Then he slips into passive-voice scientist-speak. But here's what he's trying to say: No matter how elegant a theory is, it's a baloney sandwich until it survives real-world testing.

Krauss should know. He spent the 1980s proposing formulas that worked on a chalkboard but not in the lab. He finally made his name in the '90s when astronomers' observations confirmed his seemingly outlandish theory that most of the energy in the universe resides in empty space. Now Krauss' field of theoretical physics is overrun with theorists freed from the shackles of experimental proof. The string theorists blithely create mathematical models positing that the universe we observe is just one of an infinite number of possible universes that coexist in dimensions we can't perceive. And there's no way to prove them wrong in our lifetime. That's not a Theory of Everything, it's a Theory of Anything, sold with whizzy PBS special effects.

It's not just scientists like Krauss who stand to lose from this; it's all of us. Einstein's theories paved the way for nuclear power. Quantum mechanics spawned the transistor and the computer chip. What if 21st-century physicists refuse to deliver anything solid without a galaxy-sized accelerator? "String theory is textbook post-modernism fueled by irresponsible expenditures of money," Nobel Prize-winner Robert Laughlin griped to the San Francisco Chronicle earlier this year.

Krauss' book won't turn that tide. Hiding in the Mirror does a much better job of explaining string theory than discrediting it. Krauss knows he's right, but every time he comes close to the kill he stops to make nice with his colleagues. Last year, Krauss told a New York Times reporter that string theory was "a colossal failure." Now he writes that the Times quoted him "out of context." In spite of himself, he has internalized the postmodern jargon. Goodbye, Department of Physics. Hello, String Studies.