ذراتی سریعتر از نور

طی نشستی که در اواسط هفته گذشته در شهر سانتیاگوی شیلی برگزار شد، آلفردو مورنو (Alfredo Moreno)، وزیر امور خارجه این کشور و تیم دوزیو (Tim de Zeeuw)، دبیرکل رصدخانههای جنوبی اروپا (ESO)، توافقنامهای را در خصوص احداث «تلسکوپ بیاندازه بزرگ اروپایی» (E-ELT) امضا کردند. این توافقنامه مشتمل بر تخصیص مکانی برای استقرار رصدخانه و نیز اعطای امتیاز درازمدتی بهمنظور تأسیس منطقه حفاظتشدهای در اطراف مکان مزبور همراه با حمایت دولت شیلی برای ساخت بزرگترین تلسکوپ دوران ماست.

A new type of gyroscope based on interfering atoms has been developed that can determine the latitude where the instrument is located – and also measure true north and the Earth's rate of rotation. The device has been developed by physicists in the US, who hope to scale it up so that it can test Einstein's general theory of relativity. They also want to miniaturize the technology so it can be used in portable navigation systems.

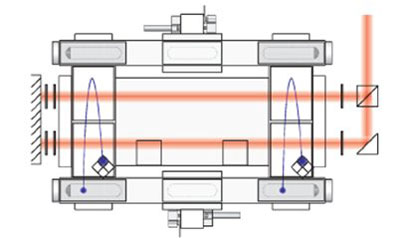

The gyroscope has been built by a team led by Mark Kasevich at Stanford University in California. It works by firing a cloud of atoms upwards at a slight angle to the vertical so that the atoms follow a parabolic trajectory as gravity pulls them down. A series of laser pulses is then fired at the cloud while in flight, which separates the atoms into a number of different bunches that follow different trajectories. The pulses are carefully selected so that two of these trajectories cross paths at a detector. Given that the atoms are governed by quantum mechanics, they behave like waves with a relative shift in phase between the atoms taking different paths. The resulting interference at the detector is dictated in part by the relative orientations of the laser pulses, gravity and the rotation of the Earth.

The device is set up so that the laser pulses are fired horizontally – that is perpendicular to gravity – and was tested by rotating the orientation of the laser pulses about the gravitational axis. The resulting interference pattern is a near-perfect sinusoid with an amplitude that depends on the Earth's rate of rotation and the latitude of the location where the measurement is made. Because we know how fast the Earth is spinning, the latitude can therefore be easily determined. The direction of true north and south are given by the direction of the laser pulses when the amplitude of the sinusoid is zero.

As the gyroscope is also sensitive to its own motion relative to its surroundings, Kasevich and colleagues have shown that it could be used for "inertial navigation", whereby the location of a vehicle (or person) is calculated by knowing its starting point and all the movements that it has made. The team demonstrated this by rotating the gyroscope about the axis perpendicular to both gravity and the laser pulses, which led to a steady change in the interference as the angular velocity was increased from zero to about 1.6 revolutions per second.

Although this is not the first atom gyroscope to be made, the team says that its dynamic range is 1000 times greater than previous versions. Another important difference between this and other atom gyroscopes is that the interference pattern does not depend on the velocity of the atoms, which means that noise and uncertainty in those measurements do not degrade its performance.

Kasevich believes that the technique could also be adapted to measure – for the first time in a laboratory setting – the tiny corrections to the trajectory of any object resulting from Einstein's general theory of relativity. "As our atom-interferometry technique essentially determines trajectory, ultimately, the interferometer phase shift should reflect those trajectory corrections related to general relativity," he says. Kasevich and colleagues now plan to refine their technique so that it is sensitive enough to measure this effect, known as "geodetic precession", and implement it in a 10 m "drop tower" that is being built at Stanford.

Although the "geodetic precession" of general relativity has previously been measured using instruments on board satellites, Holger Müller of the University of California, Berkeley thinks that "confirmation by atom interferometers would be received with great interest". However, he warns that the implementing the upgrade experiment in the 10 m tower will be "a challenge". Kasevich also has plans to implement the technology in small devices that could be used in navigation systems – and indeed is already associated with a small company called AOsense, based in Sunnyvale, California, that plans to do just that. Kasevich told physicsworld.com that a device with a volume of just 1 cm3 could be useful for terrestrial navigation applications. The current experiment is contained within a cubic magnetic shield with sides that measure about 50 cm.

Hot on the heels of this week's announcement of the physics Nobel prize "for the discovery of the accelerating expansion of the universe through observations of distant supernovae", the European Space Agency (ESA) has chosen its next two science missions, one of which will explore the nature of dark energy – which many physicists believe is the cause of the accelerating expansion. Called Euclid, this mission will study the large-scale structure of the universe with the aim of understanding how it evolved following the Big Bang. The other mission is named Solar Orbiter and will gauge the influence of the Sun on the rest of the solar system, with a special focus on the effects of the solar wind. The projects are the first in ESA's Cosmic Vision 2015–2025 plan and fall into the category of medium-class missions. There are three such missions planned for launch in 2017–2022, but the third has yet to be chosen.

In 1998 physicists were astounded by the discovery that the rate of expansion of the universe was increasing – not decreasing as had been previously thought. The cause of the acceleration remains one of the most enduring mysteries in cosmology. Euclid is a space-based telescope that aims to create the most accurate map yet of the large-scale structure of the universe. According to ESA's mission objectives, this will enable astronomers "To understand the nature of dark energy and dark matter by accurate measurement of the accelerated expansion of the universe through different independent methods."

Euclid will observe galaxies and clusters of galaxies out to redshifts of z ~ 2 at visible and near-infrared wavelengths. Its view will stretch across 10 billion light-years, revealing details of the universe’s expansion and how its structure has developed over the last three-quarters of its history. Euclid's launch, on a Soyuz launch vehicle, is planned for 2019 at Europe's Spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana.

While the Euclid mission will probe the furthest corners of the universe, the other Cosmic Vision mission will be looking at something rather closer to home. The Solar Orbiter will investigate how the Sun creates and controls the heliosphere – the bubble in space that is "blown" by the Sun and engulfs the solar system. The mission is designed to better our understanding of the influences our Sun has on its neighbourhood. In particular, it will study how the Sun generates and propels the solar wind, which is the flow of particles in which the planets are bathed. Solar activity, such as solar flares, affects the solar wind, creating strong perturbations and making it turbulent. This can have dire consequences for radio communications, satellites and space missions, as well as triggering spectacular auroral displays visible from Earth and other planets.

The Solar Orbiter will maintain an elliptical orbit around the Sun and will venture closer to it than any previous mission. This will allow the mission to measure how the solar wind accelerates over the Sun's surface and to sample this solar wind shortly after it has been ejected. The mission's launch is planned for 2017 from Cape Canaveral using a NASA-provided Atlas launch vehicle.

Early in 2004, the Cosmic Vision 2015–2025 plan identified four scientific aims: What are the conditions for life and planetary formation? How does the solar system work? What are the fundamental laws of the universe? How did the universe begin and what is it made of? A "call for missions" around these aims was issued in 2007, with Euclid and the Solar Orbiter chosen this year. ESA is now evaluating five other medium-sized missions for the final launch slot in 2022. This includes the PLATO mission, which would look at nearby stars to study the conditions required for planet formation and the emergence of life, that narrowly missed out in this latest round.

"It was an arduous task for the Science Programme Committee to choose two from the three excellent candidates. All of them would produce world-class science and would put Europe at the forefront in the respective fields. Their quality goes to show the creativity and resources of the European scientific community," says Fabio Favata, head of the Science Programme's planning office.

A common type of active galactic nuclei (AGN) could be used as an accurate "standard candle" for measuring cosmic distances – according to astronomers in Denmark and Australia. AGNs are some of the brightest objects in the visible universe and the technique could allow astronomers to determine much larger distances than is possible with current techniques, the scientists say.

Standard candles are distant objects with known brightness that give astronomers a very accurate measure of cosmic distances – the dimmer the candle appears to us, the farther away it must be. Studying these candles is crucial to our understanding of the age and energy density of the universe. Indeed, the use of supernovae and Cepheids as standard candles turned our understanding of the cosmos on its head through the discovery of the acceleration of the expansion of the universe and the introduction of dark energy.

However, reliable measurements of distances greater than redshift of about 1.7 are beyond the current capabilities of known standard candles. Now, Darach Watson and colleagues at the University of Copenhagen and the University of Queensland have shown that a tight relationship between the luminosity of an AGN and the radius of its "broad-line region" can be used to measure cosmic distances. The radius is found using "reverberation mapping", an established technique for studying the inner structure of AGNs, to gauge their mass. However, until this latest work, the method had not been considered in the search for new standard candles.

According to Copenhagen astronomer Kelly Denney, the approach works using type-1 AGNs – those with broad-line emissions in the visible spectrum. These objects have a dense area of gas and dust surrounding the black hole called the broad-line region. The region is so-called because light emitted by the gas has much broader line widths than light from most other astronomical sources.

Much closer to the black hole is the accretion disc where matter falling into the black hole collects, causing a great deal of light to be produced. As this light travels outwards, it ionizes gas in the broad-line region, causing it to emit light with the distinct broad line widths because the gas is moving at many thousands of kilometres per second due to the gravity of the black hole, and the Doppler shifts associated with this motion causes the broadening. However, the amount of light produced in the accretion disc is not constant. By carefully comparing the time at which the light is emitted from the accretion disc and the time at which the ionized light is re-emitted from the broad-line region, astronomers can measure a time lag between the light arriving from the two sources. This delay is proportional to the radius of the broad-line region divided by the speed of light. This radius correlates tightly with the luminosity of the AGN. The luminosity in turn is used to calculate the distance because they are inversely related.

The technique, however, is difficult and it wasn't until 2009 that Denney – then working with Bradley Peterson's group at Ohio State University – vastly improved the accuracy of the data from the radius-luminosity relationship such that it would allow a precise distance to be calculated. When Darach Watson came across the result, he wondered why this was not being used as a distance indicator already. "The simple answer was 'Huh, well, I don't know!' Everyone in the AGN community typically wants to know why no-one has thought of this before!" said Denney.

To confirm the technique's ability to give the distance of an AGN, Watson and colleagues looked at a sample of 38 AGNs at known distances. They found that reverberation mapping gave a reasonable estimate of the distance to the AGNs. Kenney quipped, "This almost makes the notion of AGNs as standard candles an oxymoron, since it's their variability that makes the method work!"

Currently, the AGN technique is not as reliable as those based on Cepheids or supernovae. However, unlike a supernova – which lasts for a relatively short time – an AGN can be observed over long periods, reducing observational uncertainties. Also, AGNs exist at all redshifts, so astronomers can pick and choose which ones to study. In the coming months, the researchers aim to reduce the scatter in their current data and work on higher redshift reverberation mapping experiments. "One drawback of the method is that, due to time-dilation effects, the monitoring time required to measure time delays can become very long, especially for high-redshift sources. We are investigating ways to reduce this time, such as working in the UV, where the time delays are shorter." says Denney.

The 2011 Nobel Prize for Physics has been awarded to Saul Perlmutter from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, US, Adam Riess at Johns Hopkins University, in Baltimore, and Brian Schmidt from the Australian National University, Weston Creek, "for the discovery of the accelerating expansion of the universe through observations of distant supernovae".

Perlmutter has been awarded a half of the SEK10m (£934,000) prize, with Riess and Schmidt sharing the other half. In a statement, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences said "For almost a century, the universe has been known to be expanding as a consequence of the Big Bang about 14 billion years ago. However, the discovery that this expansion is accelerating is astounding. If the expansion will continue to speed up the universe will end in ice."

Only 25 years ago most scientists believed that the universe could be described by Albert Einstein and Willem de Sitter’s simple and elegant model from 1932 in which gravity is gradually slowing down the expansion of space. From the mid-1980s, however, a remarkable series of observations was made that did not seem to fit the standard theory, leading some people to suggest that an old and discredited term from Einstein’s general theory of relativity – the "cosmological constant" or "lambda" – should be brought back to explain the data.

This constant had originally been introduced by Einstein in 1917 to counteract the attractive pull of gravity, because he believed the universe to be static. He considered it a property of space itself, but it can also be interpreted as a form of energy that uniformly fills all of space; if lambda is greater than zero, the uniform energy has negative pressure and creates a bizarre, repulsive form of gravity. However, Einstein grew disillusioned with the term and finally abandoned it in 1931 after Edwin Hubble and Milton Humason discovered that the universe is expanding.

In 1987 physicists at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the University of California at Berkeley initiated the Supernova Cosmology Project (SCP) to hunt for certain distant exploding stars, known as type Ia supernovae. They hoped to use these stars to calculate, among other things, the rate at which the expansion of the universe was slowing down. Deceleration was expected because in the absence of lambda, many people thought that "ΩM", which is the amount of observable matter in the universe today as a fraction of the critical density, was sufficient to slow the universe's expansion forever, if not to bring it to an eventual halt.

In 1998, after years of observations, two rival groups of supernova hunters – the High-Z Supernovae Search Team led by Schmidt and Riess and the SCP led by Perlmutter – came to the conclusion that the cosmic expansion is actually accelerating and not slowing under the influence of gravity as might be expected. The two teams came to this conclusion by studying type Ia supernova where they found that the light from over 50 distant supernovae was weaker than expected. This was a sign that the expansion of the universe was accelerating.

In order to account for the acceleration, about 75% of the mass-energy content of the universe had to be made up of some gravitationally repulsive substance that nobody had ever seen before. This substance, which would determine the fate of the universe, was dubbed dark energy. It is now thought that dark energy constitutes around 75% of the current universe, with around 21% being dark matter and the rest ordinary matter and energy making up the Earth, planets and stars. "The findings of the 2011 Nobel Laureates in Physics have helped to unveil a universe that to a large extent is unknown to science," stated the Academy. "And everything is possible again."

"My involvement in the discovery of the accelerating universe and its implications for the presence of dark energy has been an incredibly exciting adventure," says Riess. "I have also been fortunate to work with tremendous colleagues and powerful facilities. I am deeply honored that this work has been recognized."

Cosmologist Michael Turner from the University of Chicago says that the award to Perlmutter, Riess and Schmidt is "well deserved". "The two competing teams is a wonderful story in science – the physicists vs the astronomers," says Turner. "The biggest surprise to both teams was that the other team got the same answer. Each team believed the other didn't know what they were doing." Turner adds that before the discovery, cosmology was in some disarray with astronomers having a model of the universe based on cold dark matter and inflation, but with not enough matter to make the universe flat – a key prediction of inflation.

"Dark energy and cosmic acceleration was the missing piece of the puzzle," says Turner. "Moreover, in solving one problem, it gave us a new problem – what is dark energy? I think that is the most profound mystery in all of science." Robert Kirshner from Harvard University who supervised both Schmidt and Riess when they were PhD students says the decision by the Nobel committee is "great" as it will mean "no more waiting". "We did a lot of foundational work at Harvard and my postdocs and students made up a hefty chunk of the High-Z Team," says Kirshner. "[Riess] did a lot after the initial result to show that there was no sneaky effect due to dust absorption and that, if you look far enough into the past, you could see that the universe was slowing down before the dark energy got the upper hand, about five billion years ago."

Kirshner adds that Perlmutter is also "very deserving" of the prize. "[Perlmutter] was persistent even when his programme was moving slowly and, despite getting a contrary result in 1997, was convinced of cosmic acceleration during 1998 by comparing his own extensive data set of distant supernovae with the nearby supernovae measured by the group in Chile." Peter Knight, president of the Institute of Physics, which publishes physicsworld.com says the work has "triggered an enormous amount of research" on the nature of dark energy. "These researchers have opened our eyes to the true nature of our universe. They are very well-deserved recipients," says Knight.

Born in Champaign-Urbana, Illinois, in 1959, Perlmutter graduated from Harvard University in 1981 receiving his PhD from the University of California, Berkeley in 1986 where he worked on robotic methods of searching nearby supernovae. He then moved to the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the University of California, Berkeley. Perlmutter now heads the SCP based at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Schmidt was born in Missoula, Montana, in 1967. He graduated from the University of Arizona in 1989 and received his PhD from Harvard University in 1993 on using type II Supernovae to measure the Hubble Constant. During postdocs at Harvard, Schmidt, together with Nicholas Suntzeff from the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile, formed the High-Z Supernovae Search Team. In 1993 Schmidt then went to the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics for a year before moving to the Australian National University where he is currently based.

Riess is also a former member of the High-Z Supernovae Search Team where he lead the 1998 study that reported evidence that the universe's expansion rate is now accelerating. He was born in Washington, D.C in 1969 and graduated from The Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1992. Riess received his PhD from Harvard University in 1996 researching ways to make type Ia supernovae into accurate distance indicators. In 1999 he moved to the Space Telescope Science Institute at Johns Hopkins University.

حباب کوچکی از گرافین می تواند، یک عدسی اپتیکی با فاصله کانونی قابلتنظیم بسازد. این ادعای فیزیکدانان در انگلستان است که نشان داده اند، انحنای چنین حبابهایی می تواند با اعمال ولتاژ خارجی کنترل شود. ابزارهای ساختهشده بر مبنای این کشف می توانند در سامانههایی با کانون تطبیقی استفاده گردد تا نحوه کار چشم انسان را شبیهسازی کنند. گرافین لایهای از کربن است که تنها یک اتم ضخامت دارد و ویژگیهای بی مانند مکانیکی و الکترونیکی را داراست. بسیار کشسان است و می تواند تا 20% کشیده شود؛ یعنی با تورم آن میتواند حبابهایی با شکل های متفاوت را تولید کند. این امر در کنار اینکه گرافین ضمن اینکه برای نور شفاف است برای اکثر مایعات و گازها ناتراوا است، باعث میشود مادهای ایدهآل برای ساخت عدسیهای کانونی تطبیقی باشد.

چنین عدسیهایی در دوربین های گوشیهای تلفن همراه، وبکمها و عینکهای خود فوکوس به کار میروند و معمولا از بلورهای مایع یا سیالات شفاف ساخته میشود. اگرچه جنین ابزارهایی بهخوبی کار میکنند، ساخت آنها نسبتا دشوار و گران است. در اصل، اپتیک تطبیقی بر پایه گرافین، میتواند با استفاده از روشهای بسیار ساده تری نسبت به ابزارهای موجود، ساخته شود. همچنین، اگر فرایندهای تولید ابزارهای گرافینی در مقیاس صنعتی میسر شود، میتوان آنها را ارزانتر تولید کرد.

حبابهای بسیار کوچک

اکنون آندری گیم(Andre Geim) و کونستانتین نووسلوف(Konstantin Novoselov) – که جایزه نوبل فیزیک 2010(1389 ه.ش) را به خاطر کشف گرافین با یکدیگر تقسیم کردند- ابزارهای بسیار کوچکی ساختهاند که نشان میدهد چگونه گرافین می تواند در سامانههای اپتیک تطبیقی استفاده گردد. آنها به همراه همکارانشان در دانشگاه منچستر، در ابتدا پوستهی بزرگی از گرافین را روی زیرلایه های اکسید سیلیکون تخت قرار دادند. سپس هوایی از زیر دمیده می شود که نمیتواند از گردافین فرار کند و حبابی از ماده به طور طبیعی شکل می گیرد. حباب ها به شدت پایدار است و اندازه قطرشان از چند ده نانومتر تا ده ها میکرومتر است.

برای نشاندادن این که حبابها میتوانند به عنوان عدسی کانونی تطبیقی کار کنند، این تیم ابزارهایی ساخت که حاوی الکترودهای تیتانیوم/طلا متصل به حبابها در آرایشی شبیه ترانزیستور بودند. به این طریق، پژوهشگران قادر بودند تا ولتاژ ورودی را به چینش وارد کنند. در حالی که ولتاژ ورودی از 35- تا 35+ ولت تغییر میکند، آن ها عکسهای ساختار را از طریق میکروسکوپ نوری تهیه کردند. همانطور که انتظار میرود، همینطور که ولتاژ تغییر میکرد، آنها حبابهایی دیدند که از حالت بهشدت خمیده به حالت تختتر بروند. در واقع پژوهشگران میگویند، عدسیها در حالی کار میکردند که حبابهای گرافین با مایعی با ضریب بازتاب بالا پر شده یا حبابها با لایه تختی از این مایع پوشانده شده بودند. در مرحله بعد چه؟ نووسلوف می گوید: «ما نشان دادهایم که کنترل خمش این حبابها کار سادهای است. ما اکنون به دنبال آزمایشهای دیگری هستیم که تغییر شکلهای پیچیده تری در گرافین ایجاد کند.»

Physicists and dignitaries are gathering at Fermilab on the outskirts of Chicago to mark the final day of collisions at the Tevatron particle collider. The shutdown procedure will begin today at 2 p.m. local time, marking the end of the facility's 26-year lifetime. The shutdown comes despite calls to extend operations for a further three years, meaning that the search for the elusive Higgs boson is now likely to become a one-horse race involving the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN.

Commissioned in 1985, the facility's achievements include the discovery of the top quark in 1995. This helped the Japanese physicists Makoto Kobayashi and Toshihide Maskawa win the 2008 Nobel Prize in Physics for their prediction of the particle's existence.

Other notable discoveries made at the Tevatron are the tau neutrino in 2000; the Bc meson in 1998 and the first sighting of a single top quark in 2009. The collider, which has a circumference of more than six kilometres, also played important roles in the study of CP violation, measuring the mass of the W boson – and more recently, placing constraints on the mass of the Higgs boson.

The Tevatron collides protons with antiprotons at energies as high as 1.96 TeV, which made it the world's most energetic collider until it was usurped by the LHC in 2009. However, that did not stop physicists working on Tevatron's two main experiments – CDF and DØ – from churning out interesting results. Earlier this year, for example, particle physicists were buzzing about a mysterious "bump" that was seen in CDF data and could be evidence for a completely new particle.

Tevatron was also a centre of development of new accelerator and detector technology. The collider was the world's first major accelerator to use superconducting magnets – which allow particles to be accelerated to much higher energies than conventional magnets. During its life time, Tevatron physicists managed to boost the luminosity (collision rate) of the collider to more than 300 times that of the original design.

Fermilab's director of accelerator physics, Vladimir Shiltsev, puts this and other accelerator-related successes down to a number of key technological developments, including improvements to the Tevatron's superconducting and permanent magnets; new ways of focusing and collimating the beams; and the development of new methods of high-intensity beam manipulations, which allow physicists to split one bunch of particles into a number of smaller bunches. On the detector side, Tevatron physicists have pioneered the use of silicon vertex detectors in a hadron collider; played an important role in the development of the ring-imaging Cerenkov counter; as well as making improvements in systems that are used to track particles through the detector.

The Tevatron and its experiments produced about 1400 PhD theses and about one scientific paper per week during its 26 years. CDF and DØ are among the largest scientific collaborations ever, with a paper from either group listing more than 500 authors.

Although the groups' successes show that big science can work, not everyone is convinced that "physics by committee" is a good thing. "I'd guess that thing about the Tevatron that captivates me is that no Nobel prizes will likely be awarded for research done at the facility," says Michael Riordan, a historian of physics at the University of California, Santa Cruz (Kobayashi and Maskawa are theorists who were not involved in the experiments at Tevatron). "The top-quark discovery probably qualifies, but to what three physicists do you award it?" asks Riordan. "Doing physics by committee was a sharp break from what had occurred previously in the United States and had helped it dominate [particle] physics for three decades."

Riordan is not the only person worried about the future of particle physics in the US. There are currently no plans for a US-based replacement for the Tevatron and all eyes are now on the LHC. While many American physicists are involved in experiments at CERN, the country is not a full member of the lab. As a result, US-based particle physics could be facing a few years in the wilderness. One hope is that the International Linear Collider (ILC) – which is expected to replace the LHC – could be located at Fermilab. However, the ILC promises to be extremely expensive and funding pressures in the US and other countries could mean that the project never gets off the ground.

Meanwhile, at Fermilab, the facility is gearing up for a post-Tevatron world. The ground will soon be broken for the new Illinois Accelerator Research Center, which will see scientists and engineers from Fermilab, Argonne National Lab and Illinois universities working with industrial partners to create new technologies for accelerators.

Can particles travel faster than the speed of light? Most physicists would say an emphatic "no", invoking Einstein's special theory of relativity, which forbids superluminal travel. But now physicists working on the OPERA experiment in Italy may have found tantalizing evidence that neutrinos can exceed the speed of light.

The OPERA team fires muon neutrinos from the Super Proton Synchrotron at CERN in Geneva a distance of 730 km under the Alps to a detector in Gran Sasso, Italy. The team studied more than 15,000 neutrino events and found that they indicate that the neutrinos travel at a velocity 20 parts per million above the speed of light.

The principle of the measurement is simple – the physicists know the distance travelled and the time it takes, which gives the velocity. These parameters were measured using GPS, atomic clocks and other instruments, which gave the distance between source and detector to within 20 cm and the time to within 10 ns.

This is not the first time that a neutrino experiment has glimpsed superluminal speeds. In 2007 the MINOS experiment in the US looked at 473 neutrinos that travelled from Fermilab near Chicago to a detector in northern Minnesota. MINOS physicists reported speeds similar to that seen by OPERA, but their experimental uncertainties were much larger. According to the OPERA researchers, their measurement of the neutrino velocity is 10 times better than previous neutrino accelerator experiments.

"This outcome is totally unexpected," stresses Antonio Ereditato of the University of Bern and spokesperson for the OPERA experiment. "Months of research and verifications have not been sufficient to identify an instrumental effect that could explain the result of our measurements." While the researchers taking part in the experiment will continue their work, they look forward to comparing their results with those of other experiments so as to fully assess the nature of this observation.

Although a measurement error could be the cause of the surprising result, some physicists believe that superluminal speeds could be possible. Its discovery could help physicists to develop new theories – such as string theory – beyond the Standard Model of particle physics. However, the OPERA measurements will have to be reproduced elsewhere before they are accepted by the physics community.

Jenny Thomas of University College London, who works on MINOS, said "The impact of this measurement, were it to be correct, would be huge. In fact it would overturn everything we thought we understood about relativity and the speed of light."

Alexei Smirnov, a high-energy physicist at the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics, Italy says he finds the OPERA result “extremely surprising” as while some small deviation could have been expected, the observed deviation is very large - much larger than what is expected from even very exotic theories. “If this result is proved to be true, the consequences for modern science would undoubtedly be enormous,” he says. He agrees with conclusion of the OPERA collaboration that currently unknown systematic effects should be looked for and they should continue observations. Smirnov was one of three researchers who discovered the “matter-mass” effect that modifies neutrino oscillations in matter.

On Friday afternoon, OPERA researcher Dario Autiero from the Institut de Physique Nucleaire de Lyon discussed the details of their experiment at a seminar at CERN. Autiero addressed possible reasons for their result that took into consideration everything from inherent errors during calibration of clocks, to tidal forces and the position of the Moon with respect to CERN and Gran Sasso at the time of the readings.

They considered the possibility of problems internal to the detector itself, the chances of which OPERA say were reduced thanks to the independent external calibration methods they used. They also discussed if it would be possible to re-create the results at different energies. “We don’t claim energy dependence or rule it out with our level of precision and accuracy” said Autiero. The final note of the seminar seemed to suggest that the real reason is indeed a mystery for the time being and further analysis will definitely be required.