سومین کنفرانس ملی پیشرفتهای ابررسانایی

بعد از انتظاری ۴۵ساله، دانشمندان مرکز شتابدهنده خطی استنفورد (SLAC) وابسته به وزارت انرژی آمریکا، موفق به تولید خالصترین و کمبسامدترین لیزر پرتو ایکس شدند؛ دستاوردی که نوید موجی جدید از کشفیات علمی را میدهد.

براساس مشاهدات پژوهشگران آمریکایی، منشاء حیات چندسلولی که یکی از نقاط عطف تاریخ حیات زمینی بهشمار میرود، میتوانسته است با سرعتی حیرتآور رخ داده باشد. در این پژوهش، یک مخمر تکسلولی (موسوم به Saccharomyces cerevisiae)، تنها ظرف مدت ۶۰ روز، به اجتماعات چندسلولی منفرد بدل شد. حتی بعضی از این موجودات چندسلولی، با مرگ خود، راه را برای رشد و تکثیر دیگران فراهم آورده است و اینگونه یک فرآیند تقسیم کار ساده و ابتدایی را نیز از خودشان نشان دادند.

پژوهشی جدید نشان داده است که جهان ما به احتمال زیاد، تحت تأثیر کشش گرانشی ساختارهای عظیم و نامرئی کیهانی که در آنسوی افق جهان رؤیتپذیر ما واقع شدهاند، قرار "ندارد". دانشمندان در این بررسی، به کمک محاسبات بهدست آمده از تحلیل انفجارهای ستارهای و همچنین استفاده از قوانین فعلی علم فیزیک، دست به بازآزمایی تئوری معروف "جریان تاریک" زدند و در نهایت، اولین مدارک چالشبرانگیز علیه این فرضیه را بهدست آوردند.

کافی است به یک تکه فلز مثل نقره یا مس، نور بتابانید تا الکترونهایش برانگیخته شوند. این برانگیختگی، موجب دگرگونی میدانهای الکترومغناطیسی پیرامون الکترونها میشود و بدینواسطه، ویژگیهایی که پای فلزاتی نظیر مس را به علت رسانایی بالای آن به جهان فناوری کشانده است، خودنمایی میکنند.

Astronomers know that supermassive black holes at the centres of galaxies existed in the early universe, but how these objects managed to accumulate such heft in a short cosmological timespan is a mystery. Now, a team of researchers in Germany and the US has used a humongous computer simulation to show that cold streams of gas from outside a young galaxy could have fed its central black hole fast enough for the hole to grow rapidly.

Supermassive black holes are furnaces at the centres of galaxies. They suck in vast amounts of matter – which releases energy that causes the gas that surrounds them to glow. Astronomers call these glowing galactic centres quasars, and the UK Infrared Telescope Deep Sky Survey (UKIDSS) has found light from a quasar that was emitted as little as 800 million years after the Big Bang. This quasar and several picked up by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey are considerably brighter than expected. Indeed, they emit so much light that the black holes at their centres must have been enormous, at least a billion times the mass of the Sun.

Assuming that a supermassive black hole begins life as a relatively small black hole at the collapsed core of a massive supernova, Volker Springel of the Heidelberg Institute of Theoretical Studies in Germany says that it would need to have fed at its maximum rate from birth onwards in order to reach a billion solar masses now. "It seems possible, but it's a bit contrived," he says. This is because the rate at which a black hole accumulates matter is proportional to its mass, and therefore small black holes grow very slowly.

An alternative explanation is that a very large amount of gas – roughly 100,000 solar masses – may have collapsed directly into the black hole. Now, Springel and colleagues – including team leader Tiziana Di Matteo at Carnegie Mellon University in the US – have used a computer simulation to show that this scenario is possible.

The team modelled the universe in a virtual box 2.4 billion light-years to a side – a volume that is roughly 1% of the visible universe today. This size of simulation was chosen in order to increase the chances that extremely massive quasars would emerge from the model. Inside the box, gas and dark matter, a form of matter that interacts through gravity alone, were represented by 65.5 billion particles.

"It's a remarkable achievement to be able to simulate such a huge volume of space to the precision needed to say something about a single black hole," says Daniel Mortlock of Imperial College London. While the resolution of the study was good enough to look at individual black holes, it had to be coarse enough to make the simulation feasible. As a result, each gas "particle" had the mass of 57 million Suns, while dark matter weighed in at 280 million solar masses per particle.

The simulation covered the timespan from 10 million years after the Big Bang to about 1.3 billion years later. As time progressed, gravity caused the particles to gradually clump together. Once a congregation of gas particles reached a density associated with black-hole formation, the program introduced a particle of 100,000 solar masses into the middle of the clump to represent a black hole. This "seed" could then begin accreting gas particles according to a model of black-hole growth.

After 800 million years, one black hole had reached 3 billion solar masses, while nine more were close to the billion-solar-mass mark. To find out how they had grown, the team zoomed in on them, finding that those growing the fastest appeared to be fed by dense streams of gas. This picture supports the idea of "cold gas flows" penetrating directly to the black hole without warming up through interactions with the hot gas already in the vicinity. Although black-hole mergers have been proposed as a route to supermassive black holes, merged black holes were not among the largest in the simulation.

"[The simulation] is the first to quantitatively estimate that cold gas flows can deposit large quantities of fresh 'fuel' to the centre of galaxies, possibly feeding supermassive black holes even in absence of mergers," says Lucio Mayer of the University of Zürich, Switzerland. "However, the resolution of the simulations is still too low to ascertain if such gas would directly feed the central black hole." He suspects that it would be more likely to settle into the disc of gas surrounding the black hole, feeding it more slowly, but this detailed behaviour must be explored with higher-resolution simulations

مرکز تحقیقات تابش دانشگاه شیراز با همکاری انجمن حفاظت در برابر اشعه ایرانیان، دومین کنفرانس ایمنی پرتوهای غیریونساز را، در تاریخ 13 و 14 اردیبهشت ماه 1391، در دانشکده مهندسی مکانیک دانشگاه شیراز، برگزار میکند. محورهای این کنفرانس عبارتند از: میدانهای الکتریکی و مغناطیسی با فرکانسهای کم یا بسیار کم، پرتوهای رادیویی و مایکروویو، پرتوهای نوری (فرابنفش و فروسرخ و مرئی)، پرتوهای لیزری، فراصوت و فروصوت.

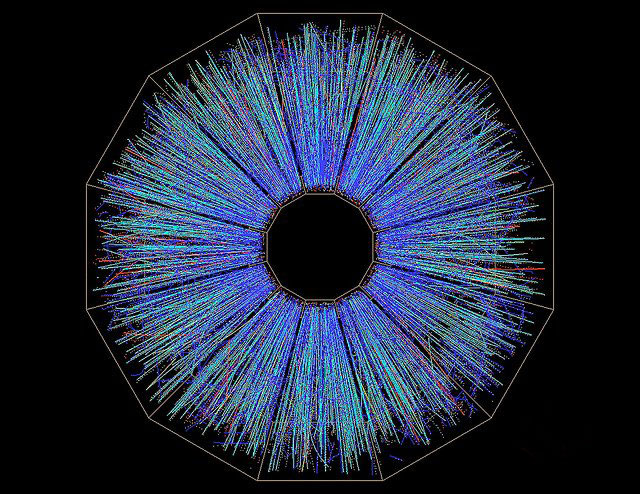

Colliding pairs of copper ions produce significantly more strange quarks per nucleon than pairs of much larger gold atoms. That is the surprising discovery of physicists working on the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) at the Brookhaven National Laboratory in the US. The finding gives further backing to the core–corona model of such high-energy collisions and could shed further light on the quark–gluon plasma – a state of matter though to have been present in the very early universe.

Quarks are normally bound-up by gluons in particles such as protons and it takes a high-energy collision to create a glimpse of free quarks. If large nuclei such as gold or lead are smashed together at high enough energies, the result is expected to be a soup of free quarks and gluons called a quark–gluon plasma. In addition to boosting our understanding of the strong force that binds quarks together, a quark–gluon plasma is thought to provide a microscopic picture of the very early universe.

When heavy nuclei are collided at RHIC, they generate a fireball that dissipates much of its energy by creating new particles. Some of these particles contain strange quarks – the lightest of the exotic quarks – and a relatively large number of strange quarks produced in a collision can imply the presence of a quark–gluon plasma. This is because an unconfined quark in a plasma behaves as if it is lighter than a quark confined in a nucleon, and this effective reduction in mass means that generating strange quarks does not take as much energy. For this reason, those hunting quark–gluon plasmas pay close attention to the number of strange quarks that crop up in particle collisions – the number should be larger than expected if the plasma is produced.

When trying to create a quark–gluon plasma, it is normally thought that the larger the nucleus, the better. As such, RHIC normally collides gold ions and the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) smashes lead. But now, physicists in the STAR collaboration at RHIC have found that copper–copper collisions produce between 20% to 30% more strange quarks per nucleon than their gold–gold counterparts. The latest study involves about 40 million copper–copper collisions and 20 million gold–gold collisions, all of which were carried out at an energy of 100 GeV per nucleon.

The copper ions contained a total of 63 nucleons – 29 protons and 34 neutrons. If their collisions produced more strange quarks than 63 proton–proton collisions at the same energy, then this is called a "strangeness enhancement", which could be evidence that the collision created a quark–gluon plasma.

There is, however, an alternative explanation for why colliding copper produces more quarks than protons. It could be that the production of strange hadrons (particles containing strange quarks) are suppressed in proton–proton collisions because of the requirement that strangeness must be conserved. Conservation rules require that for every strange quark, its antimatter version (the antistrange quark) must be produced. In collisions involving smaller nuclei, where fewer particles are generated, the burden of making extra antistrange quarks means that particles containing two or more strange quarks are harder to create. This limitation brings down the number of strange quarks generated on average in proton–proton collisions.

The team compared gold and copper collisions with the same number of "participating" nucleons. Because gold has 197 nucleons, many more than copper, the gold nuclei had to sideswipe one another rather than crash head on in order to get a collision involving 126 nucleons or less – the number involved when two copper nuclei collide. This results in an almond-shaped collection of protons and neutrons, rather than the more circular head-on copper collisions.

"The canonical picture says that the strangeness enhancement should just depend on the number of participants," says Anthony Timmins, a STAR collaborator at the University of Houston. But if that were true, the copper collisions would not have come out significantly stranger than the gold collisions.

As an alternative, the collaboration suggests that the core–corona model describes the data best. In this picture, the colliding nucleons form a core of quark–gluon plasma surrounded by ordinary nucleon–nucleon collisions. A relatively compact copper collision collects its energy in a smaller space, meaning that more nucleons join the quark–gluon plasma and produce strange quarks. Meanwhile, more nucleons in the almond-shaped gold sideswipe are lost to collisions in the corona, thus generating fewer strange quarks.

Aneta Iordanova, a former STAR collaborator who is now at the University of California, Riverside, is particularly interested in the fact that other particles – without strange quarks – also get a boost in the head-on copper collisions compared with the gold collisions. "If the particles produced in the core region dominate the particle production as a whole, then an increase in the yield of all particles, strange or not, is expected," she says.

Federico Antinori, physics co-ordinator for the ALICE experiment on CERN's Large Hadron Collider in Geneva, Switzerland, calls this a "bonus point" for the core–corona model. "It's not the final proof, but it's interesting to note that this model does rather well at explaining the data," he says. ALICE collaborators presented their first look at particles containing multiple strange quarks coming out of lead–lead collisions last year, and although quantitative comparisons with the core–corona model have yet to be made, he notes that the behaviour is qualitatively similar.

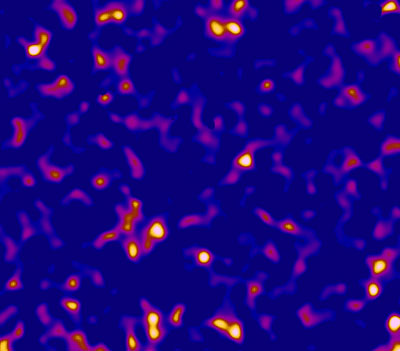

Three independent teams of astronomers have released new and improved maps of where dark matter is lurking in parts of the universe. All three groups have charted the mysterious substance by looking at how its presence distorts the images of distant galaxies as their light travels to Earth. As well as providing further insights into dark matter, the studies could provide crucial information about another mysterious substance – dark energy.

About 95% of the mass/energy content of the universe is believed to comprise dark matter and dark energy – two substances about which physicists know very little. Dark matter cannot be observed directly but is believed to make up about 23% of the mass/energy in the universe. Its existence has been inferred from the gravitational tug that it exerts on visible matter such as galaxies. Dark energy, which is also invisible, is thought to account for about 72% of the mass/energy and its existence is inferred from the accelerating expansion of the universe.

One team has used data from the Canada–France–Hawaii (CFHT) telescope to map the location of dark matter in four regions of the sky. The survey, known as CFHTLenS, includes about 10 million galaxies, which are all about six million light-years away. As the light from these galaxies travels to Earth, it is affected by the gravitational field of the dark matter that it passes along the way – a phenomenon called gravitational lensing. This distorts both the shape of the galaxies and their relative orientations as we see them on Earth – deviations that can be used to map the density of dark matter.

Observed over a period of five years, the four different patches of the sky were studied – each about 1° by 1° – using the MegaCam camera on the CFHT. The images cover a much larger area of the universe than a previous map produced by the team – which only covered 0.25° by 0.25°. The maps reveal that dark matter tends to clump around large clusters of galaxies – something that astronomers had expected but are unable to confirm in vast sections of the universe.

The team is now applying its analysis technique to data from the Very Large Telescope in Chile, which should result in much more of the sky being mapped. "Over the next three years we will image more than 10 times the area mapped by CFHTLenS, bringing us ever closer to our goal of understanding the mysterious dark side of the universe," says team member Koen Kuijken of Leiden University in the Netherlands.

The other two dark-matter maps have been made by two independent groups, both of which claim to be the first to show that "cosmic shear" measurements can be unambiguously made by ground-based telescopes. Cosmic shear is a type of gravitational lensing that makes a distant object appear stretched – turning a circular image into an elliptical one, for example. By analysing the cosmic shear of images of distant galaxies collected over nine years by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), the teams were able to create dark-matter clumps.

The teams – one largely based at Fermilab and the other at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) – have been able to improve their measurements by combining multiple snapshots of the same parts of the sky taken in the period 2000–2009. Known as "co-addition", this process helps to reduce the effects of atmospheric distortion on the shear measurements and enhance the strength of signals from very distant and very faint galaxies.

The resulting dark-matter maps could be used to gain further insights into dark energy because dark energy should have an important effect on how dark matter is distributed in the universe – in particular how it tends to clump together.

"The community has been building towards cosmic-shear measurements for a number of years now," says Eric Huff, who is a member of the LBNL team. "But there has also been some scepticism as to whether the measurements can be done accurately enough to constrain dark energy. Showing that we can achieve the required accuracy with these pathfinding studies is important for the next generation of large surveys."

براساس نظریه نسبیت اینشتین، نیروی جاذبه میتواند سیر زمان را کندتر کند. حال فیزیکدانان پی به روشی بردهاند که میتوان به کمکش اصلاً سیر زمان را متوقف کرد و یا دست کم با خماندن نور و ایجاد حفرهای در پیوستار زمان، ادای توقفش را درآورد.

این پژوهش، در امتداد تلاشهایی است که اخیراً با هدف نامرئی کردن چیزها با منحرف کردن پرتوهای نور مرئی انجام شده بود. قصه از این قرار است که اگر پرتوهای نور به جای برخورد مستقیم به یک شیئی، از کنارش عبور کنند و به عبارتی افتراق یا انعکاسی که بیننده را از وجود شیئی مربوطه خبردار میکند، اتفاق نیافتد، آنگاه آن شیئی را "نامرئی" کردهایم.

دانشمندان دانشگاه کرنل آمریکا هم از مفهوم مشابهی برای متوقفسازی زمان استفاده کردهاند، البته توقفی فوقالعاده کوتاه: چیزی در حدود ۴۰ تریلیونیم ثانیه. "مثل این میماند که بخواهید مسیر نور را در زمان منحرف کنید- یا به عبارتی از سرعتش کاسته، یا بر آن بیافزایید. در اینصورت است که میشود از نقطهنظر زمانی، یک شکاف را در پرتو نور ایجاد کرد." این را الکس گائتا (Alex Gaeta) فیزیکدان دانشگاه کرنل و از نویسندگان گزارش این یافته در نشریه علمی nature میگوید و میافزاید: "با این حساب هر واقعهای که در آن بازه زمانی رخ دهد، امکان تأثیر نهادن بر نور را پیدا نخواهد کرد و گویی که این واقعه اصلاً رخ نداده است."

Are there parallel universes? And how will we know? This is one of many fascinations people hold about quantum physics. Researchers from the universities of Calgary and Waterloo and the University of Geneva in Switzerland have published a paper in Physical Review Letters explaining why we don't usually see the physical effects of quantum mechanics.

"Quantum physics works fantastically well on small scales but when it comes to larger scales, it is nearly impossible to count photons very well. We have demonstrated that this makes it hard to see these effects in our daily life," says Christoph Simon, who teaches in the physics and astronomy department and is one of the lead authors of the paper entitled: Coarse-graining makes it hard to see micro-macro entanglement.

It's well known that quantum systems are fragile. When a photon interacts with its environment, even just a tiny bit, the superposition is destroyed. Superposition is a fundamental principle of quantum physics that says that systems can exist in all their possible states simultaneously. But when measured, only the result of one of the states is given.

This effect is known as decoherence and it has been studied intensively over the last few decades. The idea of decoherence as a thought experiment was raised by Erwin Schrödinger, one of the founding fathers of quantum physics, in his famous cat paradox: a cat in a box can be both dead and alive at the same time.

But, according to the authors of this study, it turns out that decoherence is not the only reason why quantum effects are hard to see. Seeing quantum effects requires extremely precise measurements. Simon and his team studied a concrete example for such a "cat" by using a particular quantum state involving a large number of photons.

"We show that in order to see the quantum nature of this state, one has to be able to count the number of photons in it perfectly," says Simon. "This becomes more and more difficult as the total number of photons is increased. Distinguishing one photon from two photons is within reach of current technology, but distinguishing a million photons from a million plus one is not."

به نقل از Sciencedaily

ماهیهایی هستند که جستوخیزکنان، در حالیکه بر بالههای خود ایستادهاند، از آب بیرون میزنند و حین پیادهرویشان روی خشکی، از هوای آزاد آن تنفس میکنند. بهگفته دانشمندان، از روی رفتار همین ماهیها شاید بتوان گفت که راه رفتن، قبل از مهاجرت آبزیان به خشکی، در زیر آب در عمل به تکامل رسیده است. میتوان گفت اجداد کهن انسانها و تمامی پستانداران، خزندگان، پرندگان، دوزیستان و سایر چهارپایان، در واقع ماهیانی هستند که در نهایت توانایی تنفس روی خشکی را به دست آوردهاند. یکی از اندکگونههای بقایافته از این تیرههای کهن خشکیزی، جانوران هوازی و کمیابی موسوم به "ماهی ریهدار" (Lungfish) هستند که امروزه در مناطقی از آفریقا، آمریکای جنوبی و استرالیا زندگی میکنند.