Virtual phonons get real

An acoustic analogue of the dynamical Casimir effect (DCE) has been demonstrated for the first time. Carried out by physicists in France, the experiment involves converting quantum fluctuations into pairs of quantized sound waves – or phonons – in an ultracold atomic gas. The experimental system could boost our understanding of how radiation emerges spontaneously from a vacuum. Indeed, the team is keen on modifying the set-up so it could be used to simulate Hawking radiation, a type of spontaneous vacuum radiation that is created at the edge of black holes.

One of the more peculiar aspects of quantum mechanics is that the vacuum is never truly empty. Instead it contains a small amount of energy and is buzzing with particles that appear out of nothingness, only to vanish again. One famous consequence of this is the Casimir force, where two parallel mirrors positioned close together in a vacuum experience an attractive force. While the force was first proposed in 1948 by the Dutch physicist Hendrik Casimir, it is so small that it was not measured in the lab until 1997.

Separating virtual particles

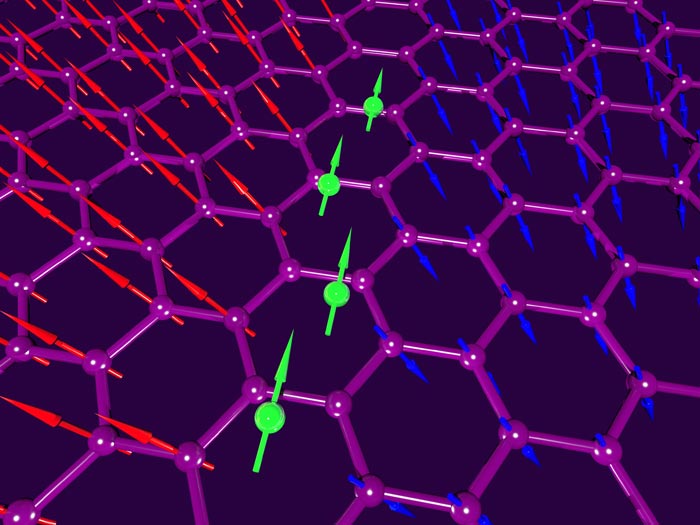

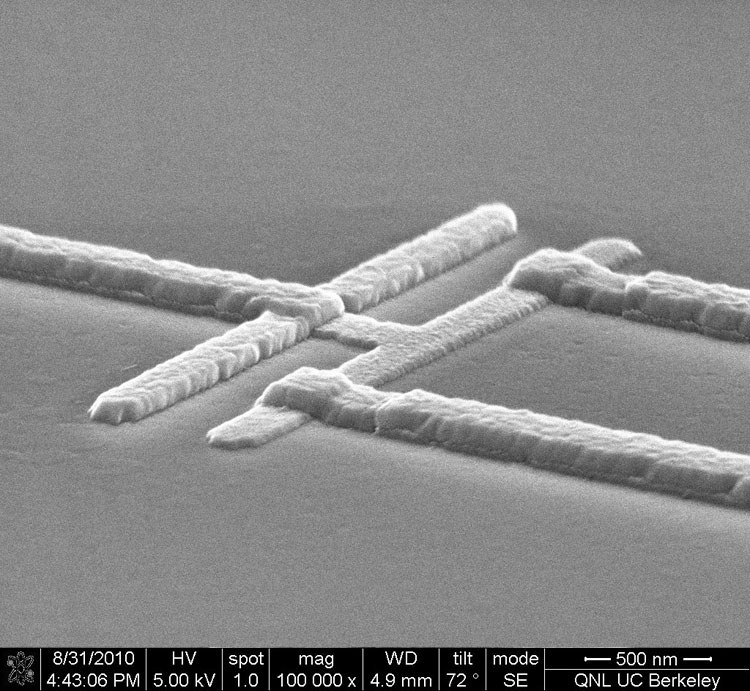

In 1970 the American physicist Gerald Moore proposed the dynamical Casimir effect, which builds on Casimir's original mirror system and shows how these virtual photons could be converted into real photons. The idea is that the phase of an electromagnetic wave goes to zero at the surface of a mirror. However, if the mirror is accelerated to a significant fraction of the speed of light, the electromagnetic field does not have time to adjust. The result is that the mirror can separate the virtual particles before they annihilate – keeping them in existence long enough to be detected. However, accelerating the mirrors to these speeds in the laboratory has so far proved impossible. To get around this problem, Chris Wilson and colleagues at Chalmers University used a superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) as an oscillating mirror – and in 2011 they claimed the first demonstration of the DCE in the laboratory.

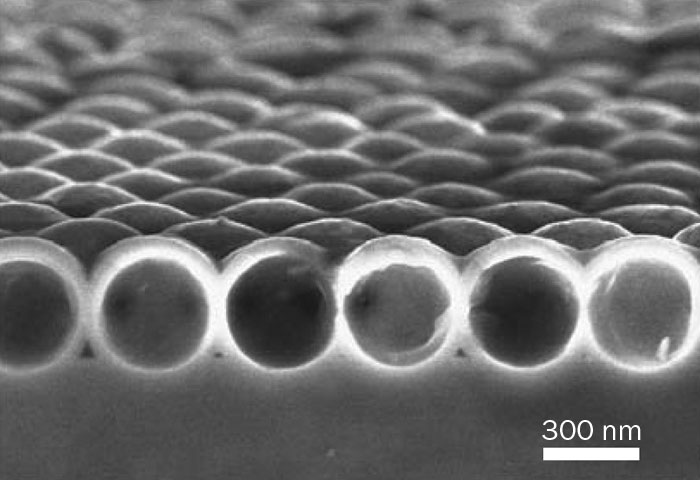

Now Chris Westbrook and colleagues at the Charles Fabry Laboratory at the University of Paris-Sud say they have created the first acoustic analogue to the DCE – which involves virtual phonons rather than photons. Their experiment was inspired by theoretical work done in 2010 by Iacopo Carusotto of Italy's University of Trento and colleagues. The Italian physicists argued that an acoustic dynamical Casimir effect should be seen in a Bose–Einstein condensate (BEC) when there is a rapid change in the scattering length that governs how its constituent atoms interact. A BEC is formed when identical bosons – particles with integer spin – are cooled until all particles are in the same quantum state. BECs are a good place to look for quantum effects because their extremely low temperature minimizes the effects of thermal noise.

Changing the speed of sound

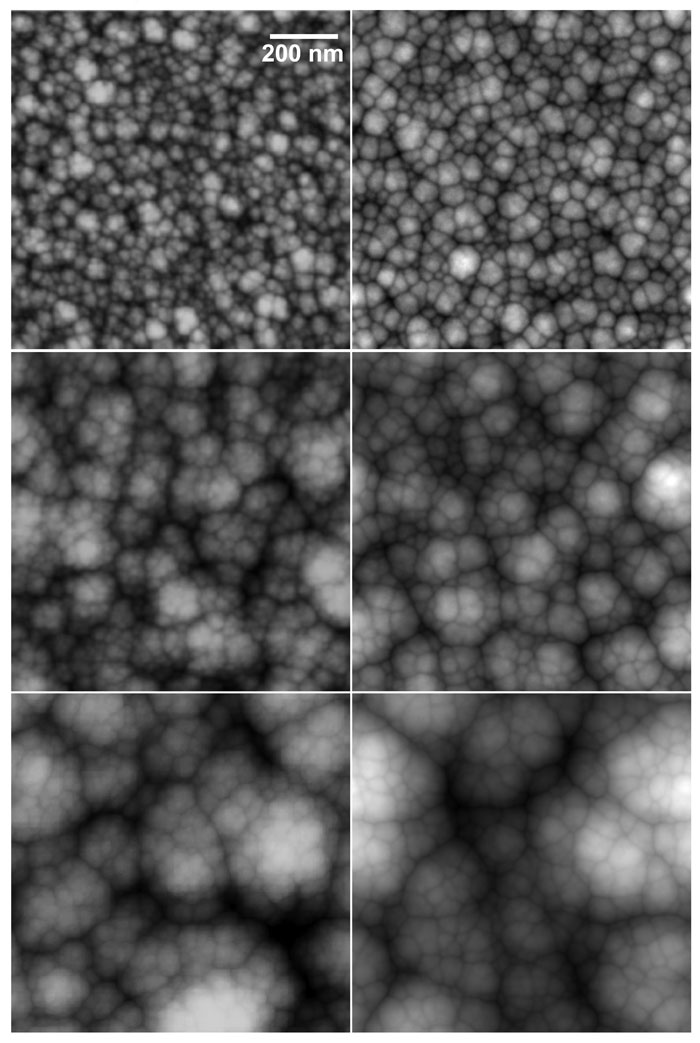

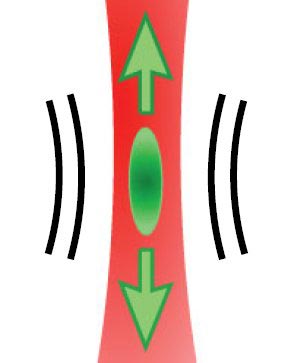

The team created its BEC by cooling about 100,000 helium atoms to about 200 nK. Instead of changing the scattering length, the team found it could achieve the DCE by changing the speed of sound within the BEC. This was done by squeezing the BEC through rapidly increasing the intensity of the laser that traps the atoms.

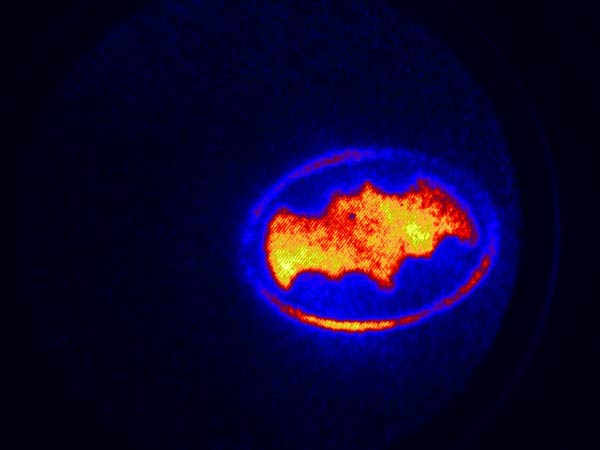

This compression causes virtual phonons to become pairs of real phonons that propagate in opposite directions. These phonons cannot be detected directly. Instead the physicists switch off the laser and then measure the velocity of the atoms as they leave the cloud. This showed that excitations with equal and opposite momenta were moving through the BEC – excitations that were not seen when the BEC was not squeezed. "Before I started doing this, I had heard of [the dynamic Casimir effect] and it sounded...unfathomably complicated," says Westbrook. "Doing this shows that it is not. It is a concrete illustration of what can happen. And once you can get your mind around it you can start modifying the conditions and thinking about other things [like] Hawking radiation."

Gobbling up sound

In 2009 Jeff Steinhauer and colleagues at the Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa produced an acoustic analogue to a black hole, which gobbles up sound instead of light. Westbrook says the team is particularly interested in combining the two systems to eventually create an acoustic analogue to Hawking radiation, a type of spontaneous vacuum radiation that takes place near the edge of black holes.

One potential flaw of the new experiment is that the DCE is seeded by thermal noise in the BEC – not by quantum vacuum fluctuations. This is because even at a chilly 200 nK, thermal effects are significant and therefore it could be argued that this experiment does not demonstrate the "pure" dynamical Casimir effect. Steinhauer agrees that the goal should be to detect correlated phonons that are seeded by quantum fluctuations. But he says the research is a "good step" toward that goal.

Daniele Faccio at Heriot Watt University in Edinburgh, UK, agrees that the most important next step is for the team to lower the temperature of the BEC. However, Faccio says he feels that the current work is still a demonstration of the physics of the DCE. "It is still a spontaneous emission of radiation, and it is a spontaneous emission that is being generated by a periodic changing boundary condition. So the physics are there," says Faccio. "I think it is a beautiful piece of work. It is extremely useful."