In a new experiment, a silica fibre just 500 nm across has been shown not to obey Planck's law of radiation. Instead, say the Austrian physicists who carried out the work, the fibre heats and cools according to a more general theory that considers thermal radiation as a fundamentally bulk phenomenon. The work might lead to more efficient incandescent lamps and could improve our understanding of the Earth's changing climate, argue the researchers.

A cornerstone of thermodynamics, Planck's law describes how the energy density at different wavelengths of the electromagnetic radiation emitted by a "black body" varies according to the temperature of the body. It was formulated by German physicist Max Planck at the beginning of the 20th century using the concept of energy quantization that was to go on and serve as the basis for quantum mechanics. While a black body is an idealized, perfectly emitting and absorbing object, the law does provide very accurate predictions for the radiation spectra of real objects once those objects' surface properties, such as colour and roughness, are taken into account.

However, physicists have known for many decades that the law does not apply to objects with dimensions that are smaller than the wavelength of thermal radiation. Planck assumed that all radiation striking a black body will be absorbed at the surface of that body, which implies that the surface is also a perfect emitter. But if the object is not thick enough, the incoming radiation can leak out from the far side of the object instead of being absorbed, which in turn lowers its emission.

Spectral anomalies spotted before

Other research groups had previously shown that miniature objects do not behave as Planck predicted. For example, in 2009 Chris Regan and colleagues at the University of California, Los Angeles reported that they had found anomalies in the spectrum of radiation emitted by a carbon nanotube just 100 atoms wide.

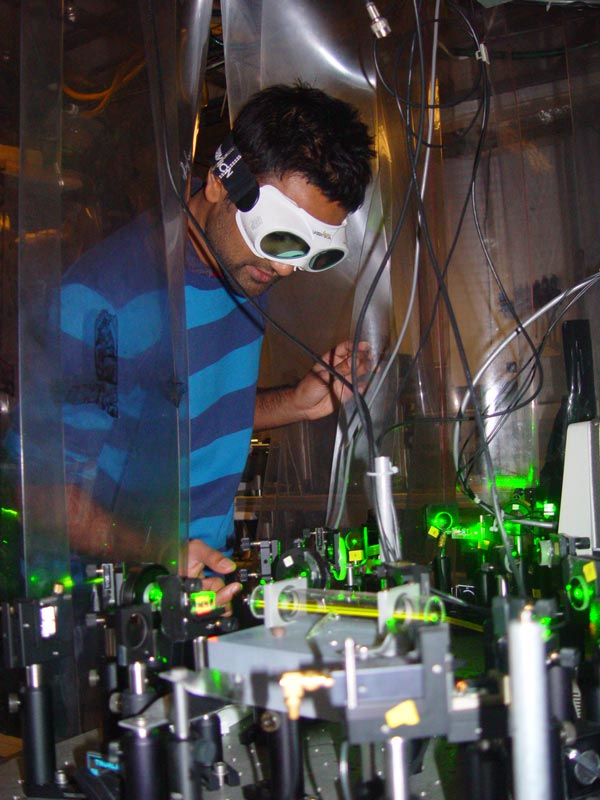

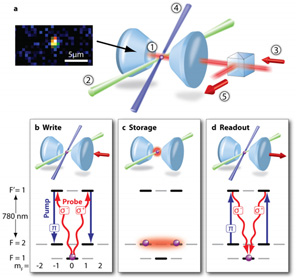

In this latest work, Christian Wuttke and Arno Rauschenbeutel of the Vienna University of Technology have gone one better by showing experimentally that the emission from a tiny object matches the predictions of an alternative theory.

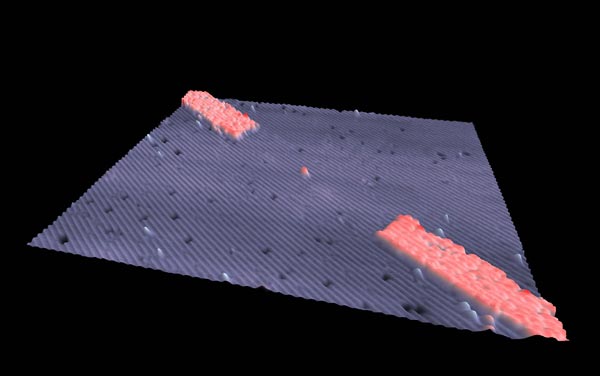

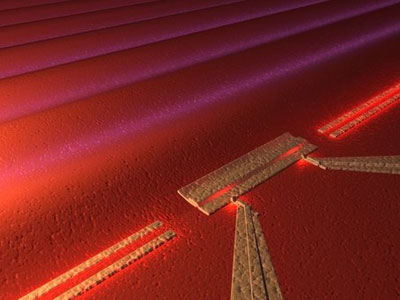

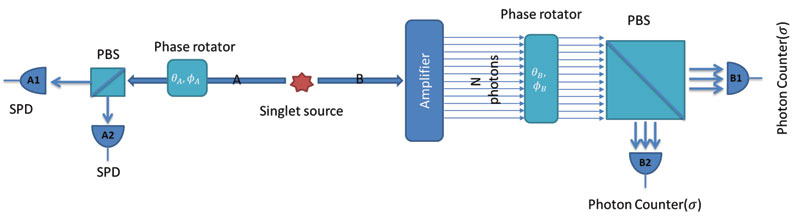

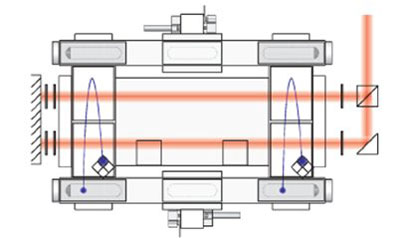

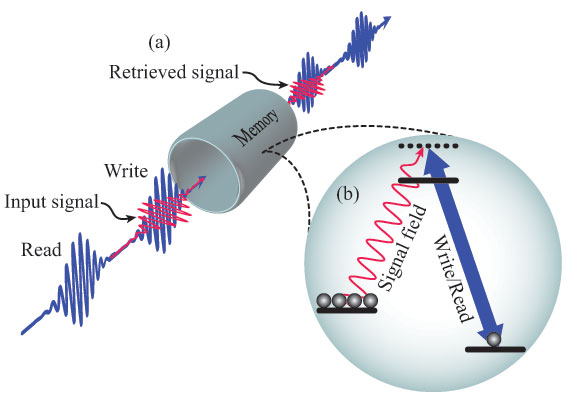

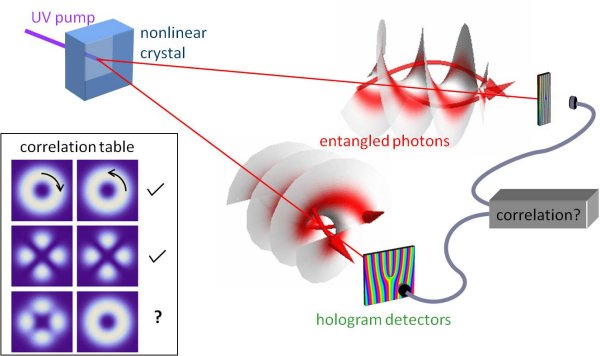

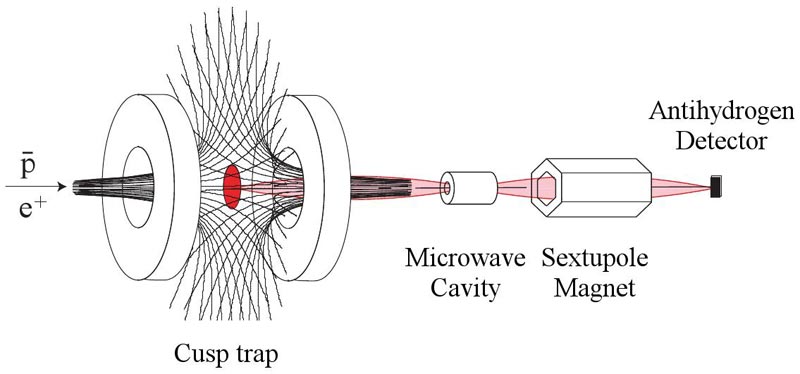

To produce the 500-nm thick fibre they used in their experiment, Wuttke and Rauschenbeutel heated and pulled a standard optical fibre. They then heated the ultra-thin section, which was a few millimetres long, by shining a laser beam through it and used another laser to measure the rate of heating and subsequent cooling. Bounced between two mirrors integrated into the fibre a fixed distance apart, this second laser beam cycled into and out of resonance as the changing temperature varied the fibre's refractive index and hence the wavelength of radiation passing through it.

Fluctuational electrodynamics

By measuring the time between resonances, the researchers found the fibre to be heating and cooling much more slowly than predicted by the Stefan–Boltzmann law. This law is a consequence of Planck's law and defines how the total power radiated by an object is related to its temperature. Instead, they found the observed rate to be a very close match to that predicted by a theory known as fluctuational electrodynamics, which takes into account not only a body's surface properties, but also its size and shape plus its characteristic absorption length. "We are the first to measure total radiated power and show quantitatively that it agrees with model predictions," says Wuttke.

According to Wuttke, the latest work could have practical applications. For example, he says that it might lead to an increase in the efficiency of traditional incandescent light bulbs. Such devices generate light because they are heated to the point where the peak of their emission spectrum lies close to visible wavelengths, but they waste a lot of energy because much of their power is still emitted at infrared wavelengths. Comparing a 500nm-thick light-bulb filament with a very short antenna, Wuttke explains that it would not be thick enough to efficiently generate infrared radiation, which has wavelengths above about 700 nm, therefore suppressing emission at these wavelengths and enhancing emission at shorter visible wavelengths. He points out, however, that glass fibre, while ideal for the laboratory, would be a poor candidate for everyday use, since it is an insulator and is transparent to visible light. "A lot of research would be needed to find a material that conducts electricity and is easily heated, while capable of being made small enough and in large quantities," he says.

Atmospheric applications

The research might also improve understanding of how small particles in the atmosphere, such as those produced by soil erosion, combustion or volcanic eruptions, contribute to climate change. Such particles might cool the Earth, by reflecting incoming solar radiation, or warm the Earth, by absorbing the thermal radiation from our planet, as greenhouse gases do. "The beauty of fluctuational electrodynamics", says Wuttke, "is that just by knowing the shape and absorption characteristics of the material you can work out from first principles how efficiently and at which wavelengths it is absorbing and emitting thermal radiation." But, he adds, here too more work would be needed to apply the research to real atmospheric conditions.

One thing that Wuttke and Rauschenbeutel are sure of, however, is that their research does not undermine quantum mechanics. Planck's theory, explains Rauschenbeutel, is limited by the assumption that absorption and emission are purely surface phenomena and by the omission of wave phenomena. His principle of the quantization of energy, on the other hand, is still valid. "The theory we have tested uses quantum statistics," he says, "so it is not in contradiction with quantum mechanics. Quite the opposite, in fact."

Regan describes the latest work as "very elegant", predicting that it will "illuminate new features of radiative thermal transport and Planck's law at the nanoscale". He suggests, however, that using an emissivity model that incorporates the transparency of the thin optical fibres would allow Planck's law to more accurately describe the radiation from these tiny emitters.