Quantum memory works at room temperature

A quantum memory for photons that works at room temperature has been created by physicists in the UK. The breakthrough could help researchers to develop a quantum repeater device that allow quantum information to be transmitted over long distances.

Quantum bits (or qubits) of information can be transmitted using photons and put to use in a number of applications, including cryptography. These schemes rely on the fact that photons can travel relatively long distances without interacting with their environment. This means that photon qubits are able, for example, to remain in entangled states with other qubits – something that is crucial for many quantum-information schemes.

However, the quantum state of a photon will be gradually changed (or degraded) due to scattering as it travels hundreds of kilometres in a medium such as air or an optical fibre. As a result, researchers are keen on developing quantum repeaters, which take in the degraded signal, store it briefly, and then re-emit a fresh signal. This way, says Ian Walmsley of the University of Oxford, "you can build up entanglement over much longer distances".

Difficult to repair

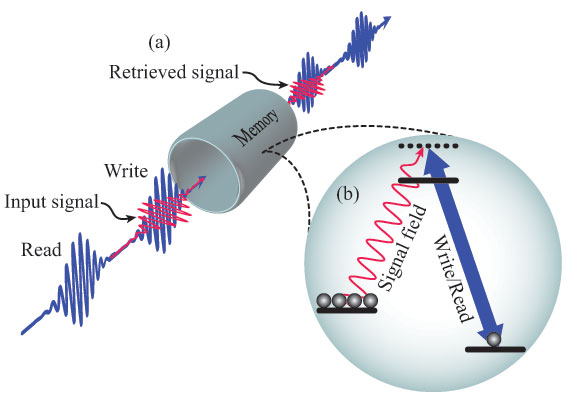

A quantum memory, which stores and re-emits photons, is the critical component of a quantum repeater. Those made so far in laboratories must be maintained at extremely cold temperatures or under vacuum conditions. They also only tend to work over very narrow wavelength ranges of light and store the qubit for very short periods of time. Walmsley and his colleagues argue that it isn't feasible to use such finicky systems in intercontinental quantum communication – these links will need to cross oceans and other remote areas, where it's difficult to send a repair person to fix a broken cryogenic or vacuum system.

Moreover, they should also absorb a broad range of frequencies of light and store data for periods much longer than the length of a signal pulse. Walmsley calls this combination a "key enabling step for building big networks". The broad range of frequencies means the memory can handle larger volumes of data, while a long storage time makes it easier to accumulate multiple photons with desired quantum states.

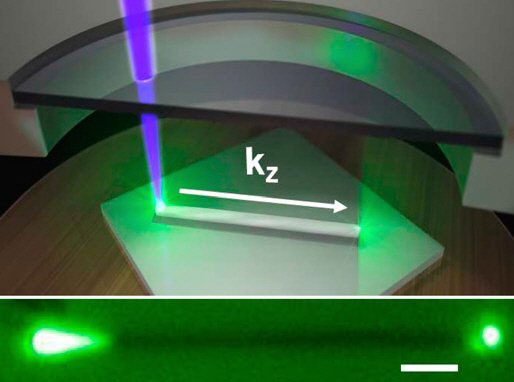

Working towards this goal, Walmsley and his team made a cloud of caesium atoms into a quantum memory that operates at an easy-to-achieve temperature of about 62 °C. Unlike previous quantum memories, the photons stored and re-emitted do not have to be tuned to a frequency that caesium electrons would like to absorb. Instead, a pulse from an infrared control laser converts the photon into a "spin wave", encoding it in the spins of the caesium electrons and nuclei.

Paint it black

Walmsley compares the cloud of caesium atoms to a pane of glass – transparent, so it allows the light through. The first laser paints the glass black in a sense, allowing it to absorb all the light that reaches it. However, instead of becoming dissipating as heat and as it would in the darkened glass, the light that passed into the caesium cloud is stored in the spin wave.

Up to 4 µs later, a second laser pulse converts the spin wave back into a photon and makes the caesium transparent to light again. The researchers say that the caesium's 30% efficiency in absorbing and re-emitting photons could increase with more energetic pulses from the control laser, while the storage time could be improved with better shielding from stray magnetic fields, which disturb the spins in the caesium atoms.

Even at 30% efficiency, Ben Buchler of the Australian National University in Canberra calls the device "a big deal" because it absorbs a wide band of photon frequencies. Due to Heisenberg's uncertainty principle, the ultra-short single-photon pulses from today's sources don't have well defined energies, so an immediately useful quantum memory must be able to absorb a wide range of frequencies – which Buchler says high-efficiency memories can't yet do.

Noise not a problem

Background noise, or extra photons generated in the caesium clouds that are unrelated to the signal photons, was a major concern for room-temperature memories. "People thought that if you started using room-temperature gases in storage mode, you'd just have a lot of noise," says Walmsley.

Temperatures near absolute zero suppress these extra photons other memories. But because the control and signal pulses in the Oxford team's set-up are far from caesium's favoured frequencies, the cloud was less susceptible to photon-producing excitations and the noise level remained small even at room temperature.

Hugues de Riedmatten of the Institute of Photonic Sciences in Barcelona, Spain, says that the researchers showed that the remaining noise is fundamental to the system, not caused by their set-up. If improvements cannot further reduce the noise, it will be challenging to maintain the integrity of the signal across a large, complex network, he explains.

Nevertheless, he says, "This approach is potentially very interesting because it may lead to a quantum memory for single photon qubits at room temperature, which would be a great achievement for quantum-information science."